For decades, paleontologist Thomas R. Holtz Jr. of the University of Maryland has been immersed in understanding dinosaurs and their ancient environments, and how these differ from our present world. His most recent investigations suggest that a critical element may have been overlooked when drawing comparisons between prehistoric dinosaurs and contemporary mammals.

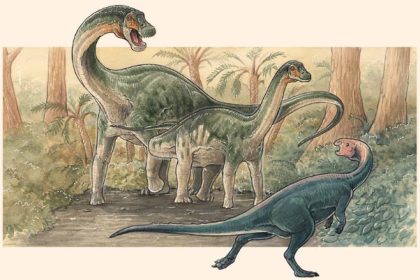

Certain sauropod dinosaurs, exemplified by Alamosaurus sanjuanensis, coalesced into age-defined herds. Image credit: DiBgd.

“Many individuals perceive dinosaurs as the mammalian counterparts of the Mesozoic era, given that both groups constituted the predominant terrestrial fauna of their respective epochs,” Dr. Holtz remarked.

“However, a fundamental divergence, largely unconsidered by scientists when assessing the differences between their respective worlds, lies in their reproductive and nurturing strategies.”

“The manner in which animals rear their progeny has a direct influence on their surrounding ecosystem, and this disparity can empower scientists to re-evaluate our perception of ecological diversity.”

“Young mammals remain under the focused care of their mothers until they are nearly fully developed.”

“Offspring of mammals essentially inhabit the same ecological niche as their parents, consuming identical food sources and interacting with the same environmental elements, because the adult individuals shoulder the majority of the strenuous activities.”

“One could characterize mammalian parenting as ‘helicopter parenting,’ particularly with a focus on the mothers,” he elaborated.

“Even when cubs reach a substantial size, comparable to their mother, a tigress will continue to hunt for them.”

“Young elephants, already among the largest creatures on the Serengeti at birth, remain dependent on their mothers and follow them for an extended period.”

“Humans exhibit a similar pattern; we provide care for our infants until they attain adulthood.”

“Conversely, dinosaurs operated under a markedly different paradigm. Although they offered a degree of parental supervision, juvenile dinosaurs were largely self-sufficient.”

“After a mere few months or a year, juvenile dinosaurs would depart from their parents and navigate their environment independently, responsible for their own sustenance and protection.”

Dr. Holtz highlighted a comparable scenario observed in adult crocodilians, which are among the closest extant relatives to dinosaurs.

Crocodiles provide protection for their nests and hatchlings for a limited duration; however, within a few months, the young disperse and adopt an independent existence, requiring several years to reach mature proportions.

“Dinosaurs exhibited characteristics more akin to ‘latchkey kids,’ as Dr. Holtz put it.

“In the fossil record, we’ve unearthed assemblages of juvenile skeletons clustered together, with no indication of adult presence.”

“These young individuals tended to congregate in groups of peers, foraging for themselves and managing their own survival.”

The “free-range” parenting approach of dinosaurs was congruent with their oviparous reproduction, resulting in the formation of relatively substantial broods in a single reproductive event.

Due to the simultaneous hatching of multiple offspring and more frequent reproductive cycles compared to mammals, dinosaurs enhanced the probability of lineage survival without demanding excessive effort or resources.

“The crucial takeaway is that this early separation of parents and offspring, coupled with the size disparities among these creatures, likely precipitated significant ecological ramifications,” Dr. Holtz stated.

“Across different life stages, a dinosaur’s diet would fluctuate, the species posing a threat would vary, and its effective range of mobility would also change.”

“Although adults and juveniles belong to the same biological species, they occupied fundamentally distinct ecological niches.

“Consequently, they could be regarded as different ‘functional species.’

For instance, a juvenile Brachiosaurus, approximately the size of a sheep, would be unable to access vegetation situated 10 meters above the ground, unlike its adult counterpart.

It would be compelled to forage in different locations, consume different plant matter, and face predation from carnivores that would typically avoid fully grown adults.

As a young Brachiosaurus progresses through various growth stages—from the size of a dog to that of a horse, then a giraffe, and finally attaining its immense mature dimensions—its ecological role undergoes continuous transformation.

“What’s particularly intriguing is that this perspective fundamentally alters how scientists conceptualize ecological diversity within those ancient worlds,” Dr. Holtz observed.

“Generally, scientists hold the view that contemporary mammalian communities exhibit greater diversity, attributed to a larger number of species coexisting.”

“However, if we consider juvenile dinosaurs as distinct functional species from their adult counterparts and recalculate the figures, the aggregate number of functional species within these dinosaur fossil communities actually surpasses, on average, that observed in mammalian ecosystems.”

Therefore, how might ancient ecosystems have sustained such a multitude of functional roles? Dr. Holtz proposes two plausible explanations.

Firstly, the Mesozoic era was characterized by different environmental conditions, including elevated temperatures and increased carbon dioxide concentrations.

These factors would have stimulated greater plant productivity, thereby generating a more abundant food supply to support a larger animal population.

Secondly, dinosaurs may have possessed metabolic rates that were lower than those of similarly sized mammals, implying a reduced caloric requirement for sustenance.

“Our current world might, in fact, be comparatively deficient in plant productivity when contrasted with the dinosaurian era,” Dr. Holtz posited.

“A more robust food chain base could have potentially sustained a greater degree of functional diversity.”

“Furthermore, if dinosaurs had a less demanding physiology, their world could have supported a significantly larger number of dinosaur functional species compared to mammalian ones.”

Dr. Holtz contends that his hypotheses do not necessarily imply that dinosaur ecosystems were substantially more diverse than our current mammalian world—rather, that diversity might manifest in forms not currently recognized by scientists.

He intends to continue investigating analogous patterns through the lens of functional diversity across various dinosaur life stages to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of their world and its evolutionary trajectory leading to the human epoch.

“We ought not to equate dinosaurs with mammals merely adorned with scales and feathers,” Dr. Holtz emphasized.

“They were unique beings about whom we are still striving to construct a complete understanding.”

His publication is featured in the Italian Journal of Geosciences.

_____

Thomas R. Holtz Jr. et al. 2026. Bringing up baby: preliminary exploration of the effect of ontogenetic niche partitioning in dinosaurs versus long-term maternal care in mammals in their respective ecosystems. Italian Journal of Geosciences 145; doi: 10.3301/IJG.2026.09