Relative to their physical dimensions, humans possess notably large brains when juxtaposed with other primates. The substantial neurological metabolic requirements for glucose may have been sustained by shifts within the gut microbial community, an entity known to exert influence over host metabolic processes. To investigate this hypothesis, our research involved seeding germ-free rodents with gut microorganisms sourced from three distinct primate taxa exhibiting variations in cranial capacity. Gene expression profiles within the brains of mice colonized with human versus macaque gut microbes demonstrated congruence with established patterns observed in actual human and macaque brains, and importantly, human gut flora facilitated augmented glucose generation and utilization within the murine cerebrum. The outcomes of this investigation imply that interspecies disparities in gut microbiota can impact cerebral metabolism, thereby proposing a potential mechanism through which the gut microbiome may have accommodated the elevated energetic demands associated with the expansion of primate brain sizes.

DeCasien et al. furnish pioneering empirical evidence illuminating the direct influence of the gut microbiome on differential primate brain functionality. Image attribution: DeCasien et al., doi: 10.1073/pnas.2426232122.

“This investigation demonstrates that microorganisms are actively affecting traits germane to our comprehension of evolution, specifically the evolutionary trajectory of the human brain,” stated Katie Amato, a researcher at Northwestern University and the study’s senior author.

This research expands upon prior discoveries, which indicated that the introduction of microbial communities from primates with more substantial brains into recipient mice resulted in enhanced metabolic energy production within the host’s microbiome—a critical prerequisite for the development and functioning of larger, more energetically expensive brains.

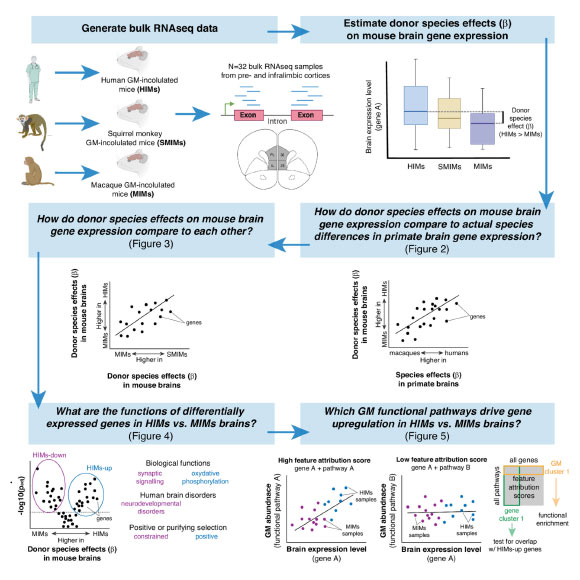

The current study aimed to scrutinize the brain itself, seeking to ascertain whether gut microbes originating from different primate species with divergent relative brain sizes could induce alterations in host mouse brain function.

Through a meticulously controlled laboratory paradigm, germ-free mice were inoculated with gut microbes derived from two primate species characterized by large brains (humans and squirrel monkeys) and one species with a smaller brain (macaques).

Following an eight-week period post-microbiome alteration, observable functional differences were detected in the brains of mice harboring microbes from smaller-brained primates compared to those receiving microbes from larger-brained primates.

In the subjects inoculated with large-brain primate microbes, scientists observed a heightened expression of genes implicated in energy generation and synaptic plasticity, the biological underpinnings of learning within the cerebral structure.

Conversely, mice colonized with smaller-brain primate microbes exhibited diminished activity in these specific neural processes.

“A particularly remarkable finding was our capacity to juxtapose the gene expression data obtained from the host mice’s brains with data derived from actual macaque and human brains. To our astonishment, a significant proportion of the brain gene expression patterns observed in the mice mirrored those identified in the primates themselves,” commented Dr. Amato.

“Put another way, we succeeded in inducing brain gene expression profiles in mice that were analogous to those of the original primate species from which the microbes were sourced.”

An equally unanticipated revelation from the researchers was the identification of a gene expression pattern associated with conditions such as ADHD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism within the genomes of mice that had been inoculated with microbes from smaller-brained primates.

While existing research offers correlational evidence linking conditions like autism to the specific composition of the gut microbiome, empirical data substantiating a causal contribution of gut microbes to the etiology of these disorders remains scarce.

“This study furnishes further support for the proposition that microorganisms may play a causal role in the development of these neurological disorders; specifically, the gut microbiome appears to shape brain development,” stated Dr. Amato.

“Extrapolating from our findings, one can hypothesize that if the developing human brain is subjected to the influence of inappropriate microbial agents, its developmental trajectory may be altered, manifesting in symptoms consistent with these disorders. In simpler terms, insufficient colonization by the ‘correct’ human microbes during early life could lead to atypical brain function and subsequently, the emergence of symptoms characteristic of these conditions.”

The outcomes of this research are published today in the esteemed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Alex R. DeCasien et al. 2026. Primate gut microbiota induce evolutionarily salient changes in mouse neurodevelopment. PNAS 123 (2): e2426232122; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2426232122