A recent contemplation of the profound statement, “God is dead, Marx is dead and I don’t feel so well myself,” prompted reflection on whether we should now append, “Nature is dead,” to this sentiment.

Has nature, conceptualized as separate from humanity, become irrelevant? Does our anthropocentric outlook, as articulated by the distinguished biologist E.O. Wilson, foster a disposition “contemptuous towards lower forms of life“?

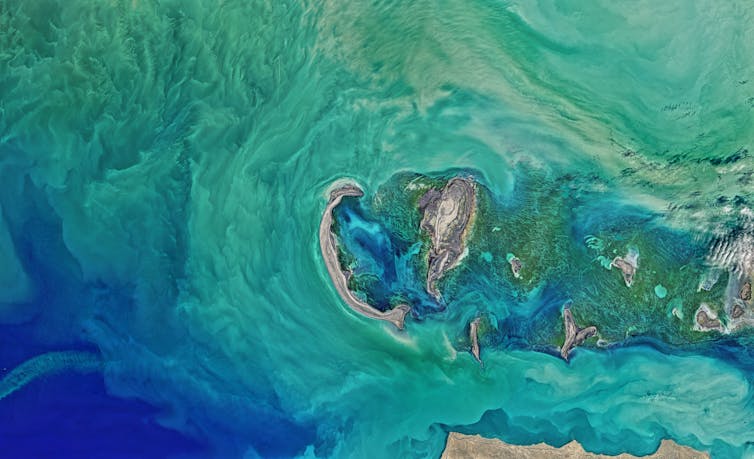

Humankind has ushered in the Anthropocene, a geological epoch where humanity stands as the preeminent agent of alteration across all ecological systems. Our pervasive impact on the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere means that no habitat remains insulated from our influence.

Whether through the pervasive colonial redistribution of species, the decimation of natural habitats, the multifaceted pressures of climate change, exhaustive resource extraction, or contamination from plastics, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and reactive nitrogen and phosphorus, the existence of an unaltered ecosystem is now a fallacy. As these disruptive forces converge, ecological systems are being propelled towards critical thresholds of collapse at an accelerated pace.

The COVID-19 global health crisis illuminated instances of reverse zoonosis, where humans served as the reservoir and vector for pathogens affecting domestic and wild fauna, underscoring the interconnected fate of humanity and all inhabitants of the biosphere.

The Perils of the Anthropocene

The advent of the Anthropocene — an era characterized by humanity’s profound planetary impact — has precipitated a global biodiversity crisis, with species disappearing at a rate 1,000 times the historical, pre-human average. Confronting this ecological emergency represents one of humanity’s most significant undertakings.

The Half-Earth initiative posits that by safeguarding 50% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface, we can ensure the preservation of 85% of its species. However, the designation of land for conservation, as seen in parks and reserves, has historically often involved the displacement of Indigenous populations, rather than acknowledging and prioritizing the pivotal role of Indigenous peoples in the stewardship of the biosphere.

While the expansion of protected territories, reaching 17% of terrestrial areas and 10% of marine environments by 2020, is a positive development, their efficacy in preserving biodiversity remains largely indeterminate. (according to the World Database on Protected Areas).

(NASA/Unsplash)

Cultivating Biodiversity Support

An emerging understanding is that biodiversity can be nurtured across all human endeavors and environments. Urban green spaces, for instance, can significantly enhance the presence of biodiversity, including vital pollinators, and agricultural landscapes can contribute positively, contingent upon the level of agricultural intensity employed.

Educational excursions for school children are increasingly shifting away from traditional nature outings towards pedagogical approaches where they cultivate a symbiotic relationship with the natural world and its inhabitants.

The English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins eloquently captured this sentiment:

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

Interconnectedness with Nature

During a facilitated breakout session at a Regeneration Canada conference, participants were prompted to define their “community.” Many offered descriptions of their urban or rural locales. My own contribution centered on my academic community—my students, my colleagues…

A young Mohawk gentleman commenced his description by identifying a stand of birch trees on his ancestral land as his community. This offered a profound contrast to the prevailing human-centric definition of community held by the others present.

According to essayist and philosopher Sylvia Wynter, the construct and undue prominence of ‘Man’—a concept originating from European Enlightenment thought and posited as separate from nature—forms the foundational ideology that facilitated historical trajectories of colonialism and racial subjugation.

Certain scholars, awakened to the profound implications of climate change, have posited that the demarcation between human history and natural history has irrevocably dissolved.

As articulated by historian Dipesh Chakrabarty in his seminal essay, “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” this dissolution of chronological boundaries signifies that central tenets of contemporary human historical narratives, such as the pursuit of liberty, are now inextricably interwoven with the destiny of the biosphere.

Consequently, historians ought to integrate their examinations of contemporary events with an understanding of our extended history as one species among countless others.

Ecological scientists are increasingly recognizing the futility of “othering” the natural world, asserting that the investigation of ecological processes must inherently incorporate those that have been influenced by human activity. Indeed, the notion of human exceptionalism—our perceived distinctiveness from all other non-human entities—is considered by some scholars to be the principal catalyst of our current global ecological predicament.

Such revised conceptual frameworks bear a closer resemblance to Indigenous perspectives on community, wherein land stewardship is undertaken in collaborative partnership with our fellow beings across all ecosystems.

Have we reached a point where the traditional understanding of nature as something distinct from ourselves is obsolete? Redefining our relationship with the natural world is a crucial undertaking that will foster a deepened commitment to addressing these anthropogenic environmental crises.

Derek Lynch, Professor of Agronomy and Agroecology, Dalhousie University