Within the frameworks of both the NOvA (NuMI Off-axis νe Appearance experiment) and T2K investigations, neutrinos are propelled from particle accelerators and subsequently detected after traversing substantial subterranean distances. The inherent difficulty is profound: from an astronomical quantity of particles, only an exceedingly small fraction leaves discernible traces. Advanced detectors and computational algorithms then meticulously reconstruct these infrequent occurrences, furnishing crucial insights into the manner in which neutrinos undergo transformations in their ‘flavor’ during transit.

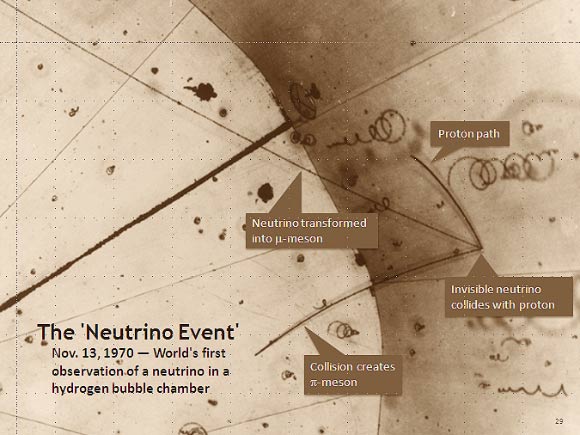

The world’s first neutrino observation in a hydrogen bubble chamber. It was found November 13, 1970, on this photograph from the Zero Gradient Synchrotron’s 12-foot bubble chamber. The invisible neutrino strikes a proton where three particle tracks originate (lower right). The neutrino turns into a mu-meson, the long center track (extending up and left). The short track is the proton. The third track (extending down and left) is a pi-meson created by the collision. Image credit: Argonne National Laboratory.

Neutrinos represent one of the most ubiquitous particulate entities in the cosmos.

Their lack of electrical charge and negligible mass render them exceptionally challenging to pinpoint. However, this very evasiveness imbues them with immense scientific value.

A comprehensive grasp of neutrino behavior could potentially illuminate one of cosmology’s most enduring enigmas: the prevailing dominance of matter in the Universe.

According to theoretical models, the Big Bang should have generated equivalent quantities of matter and antimatter, which would have subsequently annihilated each other entirely; when a particle encounters its antiparticle counterpart, both cease to exist in an energetic cascade.

Yet, at the instant of the Big Bang, a pivotal imbalance occurred, fostering a greater prevalence of matter. This asymmetry ultimately paved the way for the cosmic structures we observe today, including stars, galaxies, and life itself.

Physicists hypothesize that neutrinos may hold the key to this unresolved question.

Neutrinos exist in three distinct forms, or ‘flavors’: electron, muon, and tau, essentially representing three variants of the same infinitesimal particle.

They exhibit an extraordinary capacity to oscillate and transmute from one flavor to another as they traverse the expanse of space. The intricate mechanisms governing these oscillations, and crucially, whether they exhibit discrepancies between neutrinos and their antiparticle counterparts, could shed light on the reason why matter ultimately prevailed over antimatter in the nascent Universe.

“Investigating these varied identities can empower scientists to glean deeper insights into neutrino masses and address pivotal inquiries concerning the Universe’s developmental trajectory, including the fundamental question of why matter achieved ascendancy over antimatter in the early cosmos,” commented Dr. Zoya Vallari, a researcher affiliated with Ohio State University.

“The captivating allure of neutrinos stems from their remarkable propensity for flavor interconversion.”

“Envision procuring a serving of chocolate ice cream, embarking on a stroll, only for it to instantaneously transform into mint flavor, and with every subsequent movement, undergo yet another transformation.”

In a concerted endeavor to enhance comprehension of this dynamic, shape-shifting characteristic, the NOvA and T2K experiments have joined forces, directing concentrated beams of neutrino particles across hundreds of kilometers.

The NOvA facility propels a neutrino beam through the Earth’s crust, spanning a distance of 810 km from its origin at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, situated near Chicago, to a substantial 14,000-ton detector located in Ash River, Minnesota.

Concurrently, Japan’s T2K experiment projects a neutrino beam over a distance of 295 km, originating from the J-PARC accelerator in Tokai and terminating at the colossal Super-Kamiokande detector, nestled beneath Mount Ikenoyama.

“Although our overarching objectives were aligned, the distinct architectural designs of our respective experimental setups contribute additional layers of valuable information when our datasets are amalgamated, thereby amplifying the collective insight beyond the sum of individual contributions,” stated Dr. Vallari.

While this collaborative research builds upon prior investigations that identified subtle, yet significant, mass differences among the various neutrino species, the researchers were intent on uncovering more profound indications of neutrino behavior that deviates from the established tenets of physics.

A pertinent inquiry revolves around whether neutrinos and their antiparticle counterparts exhibit dissimilar behaviors, a phenomenon known as Charge-Parity (CP) violation.

“Our current findings underscore the imperative for acquiring additional data to sufficiently address these fundamental scientific questions,” Dr. Vallari remarked.

“This necessity underscores the critical importance of developing the subsequent generation of experimental apparatus.”

As per the revelations of the study, the integration of the outcomes from both experimental campaigns has enabled the scientific community to approach these pressing physics challenges from complementary perspectives. The co-existence of two experiments, each possessing distinct baseline distances and energy regimes, enhances the probability of achieving conclusive answers compared to the sole operation of a single entity.

“This undertaking is of extraordinary complexity, and each contributing collaboration involves hundreds of dedicated individuals,” observed Professor John Beacom from Ohio State University.

“The fact that such collaborations, which typically engage in competitive endeavors, are cooperating in this instance highlights the exceptional gravity of the scientific stakes involved.”

The seminal new findings have been formally disseminated within the esteemed journal Nature.

_____

NOvA Collaboration & T2K Collaboration. 2025. Joint neutrino oscillation analysis from the T2K and NOvA experiments. Nature 646, 818-824; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09599-3