The United Nations Accord Concerning Biodiversity Beyond Areas of National Jurisdiction, commonly referred to as the ‘High Seas Treaty,’ is set to take effect on January 17, marking a pivotal achievement in endeavors to safeguard marine life within international oceanic realms.

These oceanic expanses, designated as international waters, encompass regions of the ocean extending beyond any single nation’s exclusive economic zones (EEZs), which are typically situated within national sovereignty. Generally, EEZs extend up to 370 kilometers (230 miles) from a nation’s contiguous coastline.

These extensive territories constitute half of Earth’s surface area and two-thirds of its oceans. Despite these vast waters being rich in biodiversity and mineral resources, their absence of established sovereignty has traditionally meant a deficiency in legal safeguards. The BBNJA introduces a much-needed framework for the governance and preservation of these high seas.

The accord reached a critical juncture on September 19 of the preceding year when Morocco became the sixtieth nation to endorse it, thereby rendering it legally binding within a 120-day period. Currently, 81 UN member states have ratified the treaty, and the aforementioned 120-day timeframe is nearing its conclusion.

“Perhaps most significantly, the Agreement establishes a governance structure for the implementation of area-based management instruments (such as marine protected areas) in the high seas,” elaborated Eliza Northrop, an international environmental law specialist affiliated with the University of New South Wales in Australia, at the time the treaty’s ratification threshold was met.

“Governments are already identifying potential zones for high seas marine protected areas, encompassing locations like the Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges, the Sargasso Sea, and segments of the South Tasman Sea.”

She posits that these initial proposals will carry considerable influence, establishing a precedent for marine protected areas in international waters and, potentially more importantly, shaping the trajectory and extensiveness of future conservation initiatives. The stakes involved are substantial.

Paige Maroni, a deep-sea biologist from the University of Western Australia, stated that the treaty possesses the capacity to offer genuine protection for deep-sea and polar ecosystems, provided it is rigorously enforced.

Scientific evidence has repeatedly demonstrated that well-conceived and effectively managed marine protected areas can shield marine fauna from the impacts of carbon-intensive overfishing, which has historically led to the decimation of fish populations and inflicted irreparable harm upon ecosystems, in addition to “habitat-destroying fishing equipment, resource extraction through mining, and oil and gas exploration and exploitation,” as articulated by Grorud-Colvert and Sullivan-Stack.

Furthermore, the accord mandates that signatory parties conduct environmental impact assessments for any operations—such as fishing or mining—that could result in “substantial pollution or significant and detrimental alterations” to marine environments within international waters. This stipulation also extends to activities undertaken within a nation’s own territorial boundaries that may have ripple effects on the high seas.

Intriguingly, the treaty also institutes a mechanism for the equitable distribution of benefits derived from marine genetic resources. Currently, only a limited number of nations and corporations possess the requisite resources to harvest and commercialize the ocean’s genetic wealth (exemplified by the sea sponge that inspired chemotherapy treatments). The benefit-sharing mechanism obliges member states to disseminate the resultant proceeds.

“This mechanism encapsulates the principle that the high seas and their resources are the collective inheritance of humanity—not a domain for exclusive exploitation,” observed Northrop.

The successful realization of the BBNJA’s objectives is contingent upon adequate financial provisions, which the accord addresses by establishing three distinct funding avenues.

These include a ‘special fund’ comprising annual contributions and payments from the treaty’s participating states, alongside voluntary contributions from private entities; a dedicated trust fund to facilitate the involvement of developing nations; and the established Global Environmental Facility trust fund.

Moreover, its efficacy depends on the commitment of global leaders to adhere to scientific recommendations.

“My primary apprehension lies not with the treaty’s aspirations, but with its execution,” Maroni conveyed to ScienceAlert. “The efficacy of the High Seas Treaty will ultimately hinge on robust enforcement, adequate resourcing, and the readiness of nations to act upon scientific counsel.”

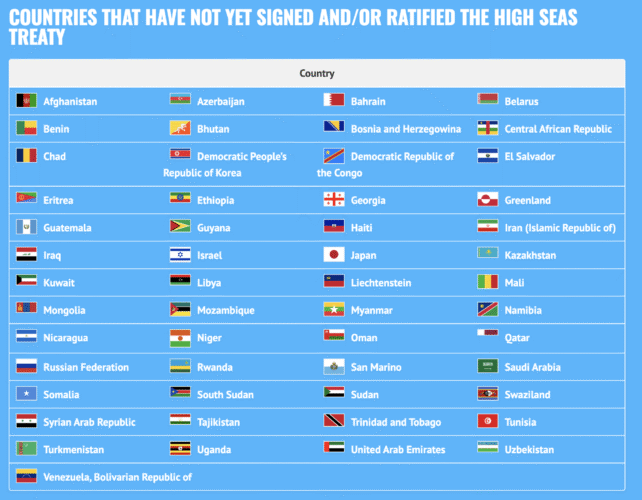

Nations such as China, the European Union, Mexico, and Vietnam are among those that have both signed and ratified the accord. Conversely, others, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, have signed but have not yet proceeded to ratification.

“Scientific input played a crucial role in the formulation and ratification of the agreement,” state Grorund-Colvert and Sullivan-Stack. “As it is now implemented, global leaders must ensure that scientific findings, rather than political considerations, continue to assume a leading role.”

A comprehensive registry of states that have signed and/or ratified the treaty is accessible via the United Nations Treaty Collection. The complete text of the BBNJ is available for review here.