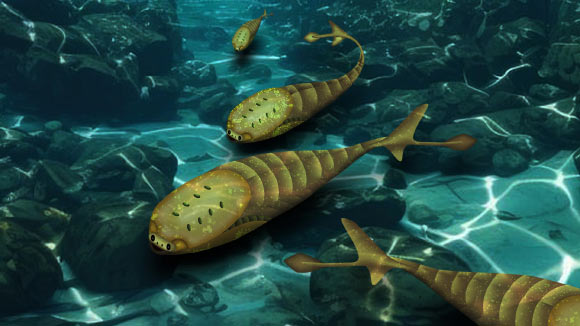

A protracted enigma within vertebrate evolutionary chronicles—specifically, the abrupt emergence of most principal fish lineages in paleontological strata considerably subsequent to their hypothesized origins—is now intrinsically linked to the Late Ordovician mass extinction (LOME), according to a novel appraisal conducted by paleontologists affiliated with the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. The researchers posited that this cataclysmic extinction event, transpiring approximately 445 to 443 million years ago, instigated parallel, geographically isolated evolutionary expansions of both jawed and closely related jawless vertebrates (gnathostomes) within distinct refugia, thereby fundamentally altering the formative history of piscine species and their extant relatives.

Life reconstruction of Sacabambaspis janvieri, a species of armored jawless fish that lived during the Ordovician period. Image credit: Kaori Serakaki, OIST.

The prevailing fossil record indicates that the majority of vertebrate evolutionary branches first materialize in the mid-Paleozoic era, a temporal period significantly postdating their Cambrian inception and the invertebrate diversification events of the Ordovician. This observed temporal disparity has frequently been ascribed to deficiencies in fossil preservation and the existence of protracted ‘ghost lineages’—periods unaccounted for by extant fossil evidence.

Conversely, Wahei Hagiwara and Lauren Sallan, paleontologists at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, propose that the Late Ordovician mass extinction profoundly reconfigured the ecological architecture of vertebrate communities.

By leveraging newly aggregated global datasets encompassing Paleozoic vertebrate fossil occurrences, their geographical distribution, and associated ecosystems, the investigators discerned that this extinction event coincided with the demise of abundant stem-cyclostome conodonts (extinct marine vertebrates lacking jaws), alongside significant losses among nascent gnathostomes and pelagic invertebrates.

In its wake, the ecosystems that emerged post-extinction witnessed the inaugural definitive appearances of most major vertebrate lineages characteristic of the Paleozoic ‘Age of Fishes.’

“While the ultimate drivers of the Late Ordovician mass extinction remain elusive, it is unequivocally evident that a distinct demarcation existed between the pre- and post-event eras, a phenomenon clearly reflected in the paleontological record,” articulated Professor Sallan.

“We meticulously synthesized two centuries of Late Ordovician and Early Silurian paleontological research, thereby constructing a novel repository of fossil data that facilitated our reconstruction of the ecological dynamics within these survival pockets,” stated Dr. Hagiwara.

“This comprehensive compilation enabled us to quantitatively assess the genus-level biodiversity of the period, thereby demonstrating how the Late Ordovician mass extinction directly precipitated a gradual yet substantial augmentation in gnathostome variability.”

The Late Ordovician mass extinction itself transpired in two distinct phases, occurring during an epoch characterized by pronounced global climatic oscillations, alterations in oceanic chemistry including vital trace elements, abrupt polar glaciation, and significant sea-level fluctuations.

These environmental upheavals inflicted severe damage upon marine ecosystems, giving rise to a post-extinction ‘hiatus’ marked by diminished biodiversity. This period of low species richness persisted well into the earliest stages of the subsequent Silurian period.

The research team’s findings corroborate a previously hypothesized interval of suppressed vertebrate diversity, known as Talimaa’s Gap.

Throughout this interval, global species richness remained exceedingly low, with the surviving faunal assemblages consisting almost exclusively of isolated microfossils.

The process of ecological recovery was protracted; indeed, the entire Silurian period represented a 23-million-year recovery phase, during which vertebrate lineages underwent gradual and intermittent diversification.

The majority of Silurian gnathostome lineages experienced a slow and discontinuous evolutionary trajectory during an initial period that otherwise saw very low global species abundance.

Rather than disseminating rapidly across the ancient marine environments, early jawed vertebrates appear to have evolved in isolated geographical pockets.

The scientific analysis revealed a pronounced degree of endemism among gnathostomes from the very outset of the Silurian period, with evolutionary diversification occurring within specific, long-enduring extinction refugia.

One such significant refugium was located in present-day South China, where the earliest definitive fossil evidence of jaw structures has been unearthed.

These pioneering jawed vertebrates remained geographically confined for millions of years.

The patterns of faunal turnover and ecological recovery following the Late Ordovician mass extinction demonstrated parallels with those observed after comparably climatically disruptive events, such as the end-Devonian mass extinction, including extended periods of limited diversity and a delayed ascendancy of jawed fishes.

“Within the geographical area presently known as South China, we observe the earliest complete fossilized specimens of jawed fishes that bear a direct evolutionary lineage to extant shark species,” remarked Dr. Hagiwara.

“These early forms were concentrated within these stable refugia for extended geological epochs until they developed the capability to traverse the open ocean and colonize other ecological zones.”

“By integrating data pertaining to geographical location, morphological characteristics, ecological roles, and biodiversity metrics, we can now definitively elucidate the mechanisms by which early vertebrate ecosystems reconstituted themselves in the aftermath of significant environmental disruptions,” stated Professor Sallan.

“This investigative endeavor contributes to our understanding of the evolutionary drivers behind the emergence of jaws, the eventual predominance of jawed vertebrates, and the genesis of modern marine life from these resilient survivors, rather than from earlier forms like conodonts and trilobites.”

This groundbreaking research was published on January 9th in the esteemed journal Science Advances.

_____

Wahei Hagiwara & Lauren Sallan. 2026. Mass extinction triggered the early radiations of jawed vertebrates and their jawless relatives (gnathostomes). Science Advances 12 (2); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aeb2297