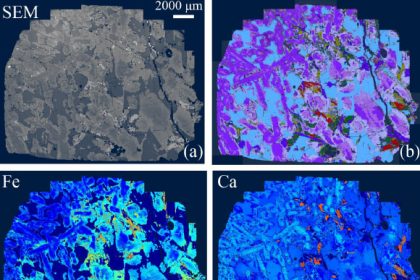

Reconstructing the Earth’s ancient geomagnetic history presents considerable difficulties, primarily due to the common phenomenon of rock magnetization being overwritten by thermal alterations during tectonic burial across their protracted and intricate geological timelines. Researchers affiliated with MIT and other institutions have discerned evidence of three distinct thermal episodes impacting rocks from the Isua Supracrustal Belt in West Greenland. The most significant of these events, occurring approximately 3.7 billion years ago, elevated rock temperatures to as high as 550 degrees Celsius. Subsequent thermal influences in the northernmost sector of the study area did not elevate temperatures beyond 380 degrees Celsius. To substantiate these findings, the authors have marshaled a convergence of evidence, including paleomagnetic assessments, the spectrum of metamorphic mineral assemblages throughout the region, and the thermal thresholds at which radiometric dating of observed mineral populations was reset. By integrating these diverse data streams, they posit that an ancient geomagnetic signature, dating back 3.7 billion years, may endure within the banded iron formations located in the northern confines of the surveyed territory.

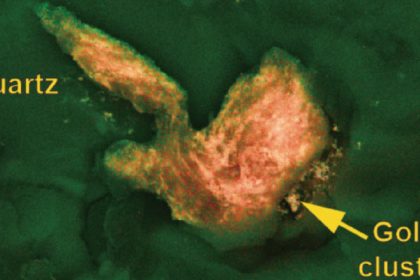

In their recent investigation, Professor Claire Nichols of the University of Oxford, in collaboration with her colleagues, scrutinized an archaic stratum of iron-rich rocks originating from Isua, Greenland.

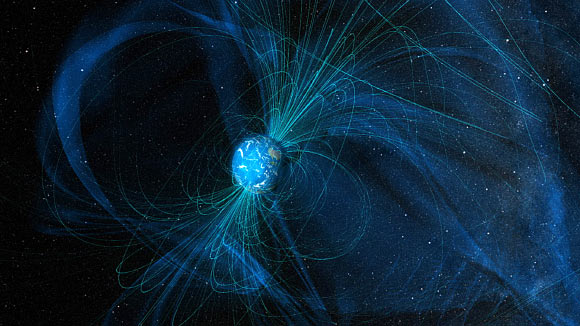

Particles of iron serve as miniature compasses, capable of imprinting both the strength and orientation of the magnetic field at the moment their crystalline structure solidifies.

The investigative team determined that rock samples dating back 3.7 billion years recorded a geomagnetic intensity of at least 15 microtesla, a value comparable to the contemporary magnetic field’s strength of 30 microtesla.

These findings represent the most ancient quantitative estimation of Earth’s magnetic field strength derived from intact rock specimens, offering a more robust and dependable evaluation than prior analyses focused on individual mineral crystals.

“Extracting credible historical data from such ancient geological formations is an exceptionally formidable undertaking, and the emergence of primary magnetic signatures during our laboratory analyses was profoundly exhilarating,” Professor Nichols commented.

“This represents a crucial advancement in our ongoing efforts to ascertain the influence of the primordial magnetic field during the nascent stages of life’s evolution on Earth.”

While the magnitude of the magnetic field appears to have remained relatively stable, it is a known fact that the solar wind was considerably more intense during prehistoric eras.

This observation implies an enhancement in the planet’s atmospheric shielding against solar radiation over geological epochs, potentially facilitating the migration of life from oceanic refuges to continental landmasses.

The generation of Earth’s magnetic field originates from the convective motion of molten iron within the liquid outer core, a process propelled by buoyancy forces arising from the solidification of the inner core, thereby establishing a geodynamo.

During the planet’s embryonic stages, the absence of a solidified inner core raises pertinent questions regarding the mechanisms sustaining the nascent magnetic field.

The current findings suggest that the energetic driver of Earth’s early geodynamo evinced a degree of efficiency comparable to the solidification process responsible for the planet’s current magnetic field generation.

An understanding of historical fluctuations in Earth’s magnetic field intensity is also pivotal for pinpointing the commencement of the Earth’s solid inner core’s formation.

This knowledge will contribute to unraveling the rate at which thermal energy dissipates from Earth’s deep interior, a crucial factor in comprehending phenomena such as plate tectonics.

A significant hurdle in reconstructing Earth’s magnetic field from such remote antiquity lies in the susceptibility of preserved magnetic signals to alteration by any thermal event experienced by the rock.

Rocks within the Earth’s crust often possess lengthy and complex geological histories that tend to obliterate prior geomagnetic information.

Nevertheless, the Isua Supracrustal Belt exhibits a distinctive geological characteristic: its emplacement atop substantial continental crust provides a degree of protection from extensive tectonic disturbances and structural deformation.

This unique geological circumstance enabled the scientific team to construct a compelling body of evidence supporting the existence of a magnetic field 3.7 billion years ago.

Furthermore, these discoveries may illuminate the role of our planet’s magnetic shield in shaping the evolution of Earth’s atmosphere as we know it, particularly concerning the atmospheric loss of gases.

“Looking ahead, we aspire to broaden our comprehension of Earth’s magnetic field preceding the significant rise in atmospheric oxygen approximately 2.5 billion years ago by examining other ancient rock sequences located in Canada, Australia, and South Africa,” the authors stated.

“A more profound grasp of the ancient strength and variability of Earth’s magnetic field will assist us in determining whether planetary magnetic fields are indispensable for supporting life on a planet’s surface and their influence on atmospheric development.”

The investigation was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

_____

Claire I. O. Nichols et al. 2024. Possible Eoarchean Records of the Geomagnetic Field Preserved in the Isua Supracrustal Belt, Southern West Greenland. Journal of Geophysical Research 129 (4): e2023JB027706; doi: 10.1029/2023JB027706