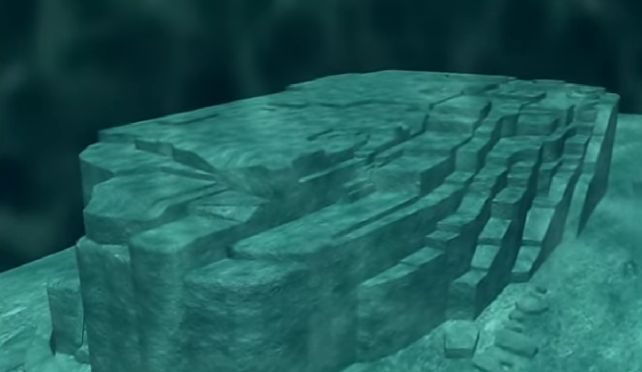

Beneath the cerulean expanse of the ocean adjacent to Japan’s Yonaguni Island lies an extraordinary geological enigma.

With its uppermost stratum positioned merely 6 meters (20 feet) beneath the ocean’s surface and descending to a depth of 24 meters, the Yonaguni Monument presents an appearance remarkably akin to an immense, submerged citadel, seemingly a vestige of an ancient civilization swallowed by the sea.

However, the prevailing geological consensus posits a different origin; its stratified composition of sandstone and mudstone is understood to be a product of natural forces, meticulously sculpted by fault lines, bedding planes, geological stresses, and the ceaseless action of erosion.

This remarkable formation was brought to light in 1987 by diving instructor Kihachiro Aratake, rapidly capturing the interest of the scientific community. It stood apart from many other geological structures familiar to researchers, particularly in its imposing scale and its surprisingly ordered configuration.

The monument is characterized by substantial stone slabs, arrayed in a manner reminiscent of terraces or steps, exhibiting precisely defined edges and corners. Such geometric regularity is unusual for natural formations of this magnitude, prompting associations with stepped pyramids or ziggurats.

The sheer impact of its appearance led geologist Masaaki Kimura of the University of the Ryukyus to dedicate several years to assembling comprehensive evidence. He argued for the structure’s human modification or construction, postulating its submersion due to sea-level rise approximately 10,000 years ago.

This hypothesis is met with considerable skepticism within the broader geological fraternity.

While dedicated peer-reviewed investigations into the Yonaguni formation are relatively scarce, a substantial body of geological data indicates that its peculiar, structured aspect can be accounted for by natural geological processes operating over millennia.

It is well-established that our planet is capable of producing extraordinarily geometric rock formations.

The iconic hexagonal columns found at Ireland’s Giant’s Causeway and Scotland’s Fingal’s Cave serve as prime examples, embodying the very essence of natural marvels.

Furthermore, Tasmania, Australia’s Tessellated Pavement appears as meticulously arranged flagstones at the oceanic fringe, while the Al Naslaa rock in Saudi Arabia is bisected by an astonishingly clean, straight fissure.

Norway’s Preikestolen, or Pulpit Rock, is renowned for its sheer, flat geological profile.

Several natural geological phenomena and processes bear relevance to the Yonaguni formation.

A bedding plane represents a natural stratification within sedimentary rocks such as sandstone and mudstone. It signifies the interface between distinct depositional periods, separating rock layers with differing characteristics. These planes are frequently flat and constitute inherent planes of weakness within a rock mass.

Perpendicular to these bedding planes, rock formations can develop joint sets. These are fissures within the structure, often exhibiting a high degree of parallelism, which propagate when the rock experiences stress—such as seismic activity—thereby segmenting the rock into remarkably precise blocks.

As observed by geologist Robert Schoch from Boston University, who explored the site in 1997, “Yonaguni is situated in a seismically active zone; such earthquakes tend to fracture the rocks in a systematic manner.”

Given that Yonaguni is located within a fault zone, it is subject to considerable seismic activity, which could readily account for both the regularity of the fractures and the stepped morphology.

When seismic forces agitate the ground beneath the formation, the rocks fracture and displace along these inherent lines of weakness—processes that can yield the characteristic shape of the Yonaguni Monument.

Concurrently, the persistent motion of ocean currents contributes to the erosion of these fractures, gradually separating the rock masses and smoothing their surfaces.

Schoch also noted that adjacent rock formations on Yonaguni Island, though more rounded and significantly weathered, exhibited a similar arrangement to the submerged structure.

“Although the slope itself, now a chaotic expanse of jagged, fractured planes,” wrote the late author John Anthony West, who investigated alongside Schoch, “did not strongly resemble the underwater formation we had been studying, it was evident that it represented fundamentally the same geomorphology—simply that the slope, subjected solely to wind and precipitation, had acquired a vastly different and rugged appearance over millennia.”

The inherent challenges and substantial costs associated with underwater geological research, coupled with the fact that all aspects of the Yonaguni Monument and its surrounding geological context can be elucidated by natural processes, have historically limited more extensive investigations at the site.

However, a geological team led by Hironobu Suga of Kyushu University, presenting at the 2024 Association of Japanese Geographers Spring Academic Conference, stated, “While these formations were once presumed to be artificial, no archaeological artifacts or evidence of human activity have been unearthed.”

“Through subaquatic observations, we were able to document erosional processes, including bedrock detachment, abrasion, and the generation of gravel, along with the ongoing development of erosional features, such as potholes of varying dimensions.

“These findings strongly suggest that the monument’s ruin-like appearance is a direct result of the continuous weathering and erosion of seafloor sandstone.”

And in truth, the sheer capacity of Earth to sculpt such breathtaking structures through the simple passage of time and seismic activity is profoundly captivating in itself.