The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR), which presents itself as “the definitive voice of the stem cell research community,” has issued a declaration indicating that it no longer upholds the prevailing global consensus that restricts human embryo investigations to a maximum of 14 days post-fertilization.

The exploration of human embryos has historically been a profoundly complex ethical quandary, stemming from conflicting perspectives on the moral standing of the nascent embryo. Certain viewpoints posit that human embryos possess the moral equivalence of sentient beings and warrant protection as vital human life, advocating against their utilization in research, particularly when such studies lead to their destruction.

Conversely, other perspectives challenge these assertions, emphasizing the significant potential scientific and therapeutic advancements achievable through research involving human embryos.

These advancements include gaining insights into human embryogenesis, the proliferation of cancerous cells, the etiology of congenital disorders, and the underlying causes of pregnancy loss. The practical applications derived from such research encompass the development of novel contraceptives, the accurate diagnosis of genetic anomalies, and the treatment of infertility and other medical conditions.

Prior to this recent update, the ISSCR directives issued in 2016 expressly forbade the cultivation and use of embryos beyond the 14-day developmental milestone.

The updated guidelines, unveiled on May 26, have rescinded this prohibition. Instead, the ISSCR advocates for “national science academies, academic consortiums, funding bodies, and regulatory authorities” to initiate broad public discourse regarding the scientific, societal, and ethical implications surrounding the 14-day boundary, and to consider its potential extension contingent upon specific research objectives.

Historical Context of the 14-Day Rule

The 14-day rule, also referred to as the 14-day limit, “crystallized as a foundational element of embryo research oversight through the cumulative deliberations of various national committees over several decades.”

Currently, disparate national regulations exist, reflecting varying degrees of alignment with the competing viewpoints on the moral status of human embryos. Several nations, including Austria, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Turkey, impose prohibitions on research involving human embryos.

Other countries, such as Canada, China, India, Japan, Spain, and the United Kingdom, permit restricted human embryo research up to the 14-day mark, without exceeding it. Still other jurisdictions, for instance Brazil and France, allow such research without imposing any temporal limitations.

In 1979, following comprehensive public consultations, the Ethics Advisory Board of the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare published a report advocating for judicious human embryo research. The board concluded that such investigations should be permissible, provided the embryos were not “sustained in vitro beyond the developmental stage typically associated with the successful implantation (14 days post-fertilization).”

Five years later, also after extensive public deliberation, the Warnock Report from the UK’s Committee of Inquiry into Human Fertilisation and Embryology reached a comparable conclusion. However, the emphasis within this report centered on a distinct biological marker: the emergence of the primitive streak (a precursor to the central nervous system), which manifests on the 14th or 15th day following fertilization.

The foundational national legislation codifying the proposed ethical threshold of 14 days was enacted in the UK via the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act of 1990. Subsequently, numerous countries (with the exception of the United States) have adopted similar statutory provisions.

In Canada, the Assisted Human Reproduction Act of 2004 explicitly prohibits any individual from knowingly “maintaining an embryo outside the body of a female person beyond the 14th day of its development subsequent to fertilization or creation, excluding any period during which its development has been arrested.”

Until this recent modification, the ISSCR’s guidelines were consistently aligned with existing laws, regulations, and ethical frameworks that endorsed the 14-day limit. This alignment has now been discontinued.

Justification for the Prohibition

The decision to abandon the established 14-day rule represents a misstep. There are valid grounds to advocate for public discourse and debate concerning the merits of this particular rule. However, there is no justifiable rationale for directing this discussion solely towards extending the research timeline. For instance, an equally valid public conversation could address the possibility of shortening, rather than lengthening, the permissible research duration.

More critically, there is no legitimate reason to have withdrawn the 14-day rule prior to engaging in any public consultation that might ultimately affirm the existing limit or propose an alternative policy. Such an action alters the current regulatory landscape, both in principle and potentially in practice.

For example, nations lacking pertinent legislation, regulatory frameworks, or guidelines risk becoming conduits for ethically contentious human embryo research conducted beyond the 14-day threshold.

Indeed, the authors of the 2021 ISSCR guidelines assert that in jurisdictions where legislative measures are absent or where existing statutes contain “significant deficiencies and ambiguities,” “carefully crafted guidelines can serve a crucial function for scientists and clinicians engaged in research and patient care.” The recently revised guidelines can no longer fulfill this protective role for embryo research extending beyond 14 days.

Evolving Scientific Capabilities and Limitations

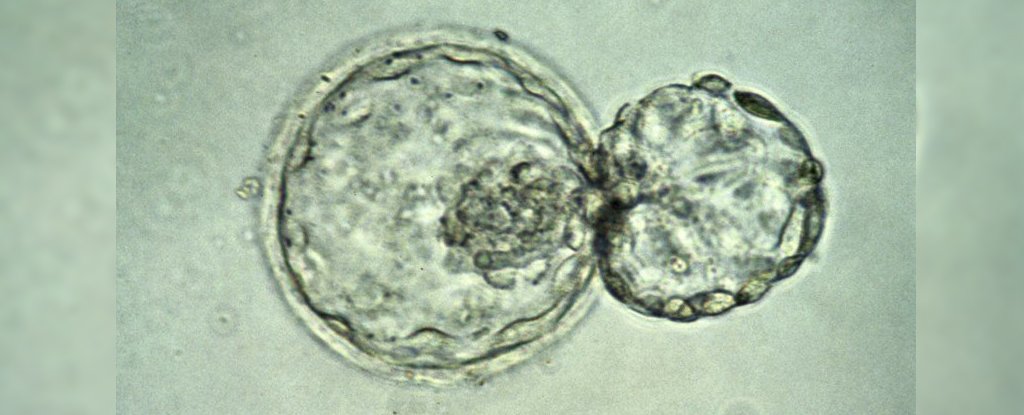

Until recently, researchers lacked the capacity to sustain human embryos in laboratory settings for periods exceeding 14 days, rendering the established limit practically moot. However, in 2016, two distinct research teams—one affiliated with the University of Cambridge in the UK and the other with Rockefeller University in the US—achieved success in maintaining human embryos in vitro for durations of 12 to 13 days. Although these experiments could have been prolonged, they were curtailed in adherence to the 14-day rule.

The research conducted in the UK explicitly cited the relevant legislation as the basis for terminating the experiments. In contrast, the research undertaken in the United States, which lacks comparable legislation, made direct reference to the ISSCR guidelines.

Since that time, discussions within academic spheres regarding the validity of the 14-day rule have intensified. Now that the technical impediments have been surmountable, there is a discernible drive to revise the ethical constraints.

One proposed approach involves “maintaining the 14-day rule while instituting a special petition process for exceptions.” Another suggestion advocates for extending the temporal limit to 28 days, thereby affording researchers greater opportunities to investigate embryonic developmental processes.

My recommendation, as an ethicist operating at the nexus of policy and practical application, is to implement project-specific timelines calibrated to the minimum duration requisite for achieving the articulated research objectives. This approach could result in some human embryo research being curtailed before reaching day 14, while other investigations might be permitted to continue beyond that point.

Categories of research with distinct temporal limits could be delineated within international or national ethical guidelines for research and subsequently codified into national legislation. Alternatively, national regulations and guidelines might articulate only the overarching intent, with decisions on project-specific durations falling under the purview of specialized national research ethics committees.