Our planet has undergone profound climatic transformations across its existence, alternating between frigid “icehouse” epochs and balmy “greenhouse” eras.

For an extended period, researchers have correlated these atmospheric alterations with variations in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. Nevertheless, contemporary investigations are illuminating the origins of this carbon—and the mechanisms governing its flux—as considerably more intricate than previously comprehended.

Indeed, the terrestrial locomotion of tectonic plates exerts a substantial, hitherto underestimated influence on climatic patterns. Carbon is not solely liberated at the junctures where tectonic plates interface. The loci where these plates recede from one another are equally consequential.

Our recent scholarly contribution, disseminated today within the esteemed journal Communications, Earth and Environment, elucidates precisely how Earth’s plate tectonics have been instrumental in sculpting global climate over the preceding 540 million years.

Delving into the Depths of the Carbon Cycle

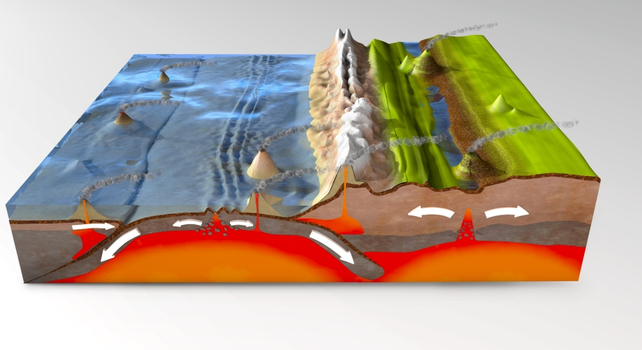

At the convergent boundaries of Earth’s tectonic plates, chains of volcanoes, known as volcanic arcs, are fashioned. The magmatic activity associated with these volcanic formations facilitates the release of carbon, entombed within lithic structures for millennia, transporting it to the planet’s surface.

Historically, it was posited that these volcanic arcs were the principal agents responsible for the infusion of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Our findings contravene this established perspective. We propose, instead, that mid-ocean ridges and continental rifts—zones characterized by the divergence of tectonic plates—have exerted a far more significant influence on the Earth’s carbon dynamics throughout geological epochs.

This assertion stems from the oceans’ prodigious capacity to sequester atmospheric carbon dioxide. The majority of this carbon is entombed within carbon-rich strata on the ocean floor. Over extended geological timescales, this process can engender hundreds of meters of carbonaceous sediment accumulation at abyssal depths.

As these lithic formations are subsequently transported by the inexorable movement of tectonic plates, they may eventually encounter subduction zones—regions where tectonic plates converge. This phenomenon results in the expulsion of their sequestered carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere.

This intricate process is identified as the “deep carbon cycle.” To trace the peregrinations of carbon between Earth’s molten interior, its oceanic lithosphere, and the atmosphere, computational models simulating the migration of tectonic plates through geological time can be employed.

Investigative Findings

By leveraging computational simulations to reconstruct the terrestrial movement of carbon stored within tectonic plates, we successfully projected significant greenhouse and icehouse climatic episodes spanning the last 540 million years.

During periods of elevated global temperatures, commonly referred to as greenhouse states, the exhalation of carbon surpassed its assimilation within carbon-bearing geological formations. Conversely, during icehouse climatic conditions, the sequestration of carbon into Earth’s oceans predominated, thereby diminishing atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations and precipitating a cooling trend.

A paramount revelation from our investigation underscores the indispensable function of deep-sea sediments in modulating atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. The slow, persistent motion of Earth’s tectonic plates facilitates the transport of carbon-laden sediments, which are ultimately reincorporated into Earth’s interior via the geological process of subduction.

Our analysis demonstrates that this mechanism constitutes a principal determinant of whether Earth exists in a greenhouse or icehouse climatic regime.

A Re-evaluation of Volcanic Arc Contributions

Historically, the carbon efflux emanating from volcanic arcs has been regarded as a primary contributor to atmospheric carbon dioxide.

However, this phenomenon only achieved preeminence in the last 120 million years, largely attributable to the proliferation of planktic calcifiers. These microscopic marine organisms, belonging to a family of phytoplankton, possess the remarkable ability to transmute dissolved carbon into calcite. Their activity is responsible for sequestering immense volumes of atmospheric carbon into recalcitrant sediment deposited on the ocean floor.

Planktic calcifiers emerged approximately 200 million years ago and achieved widespread distribution throughout Earth’s oceans around 150 million years ago. Consequently, the substantial proportion of carbon released into the atmosphere via volcanic arcs over the past 120 million years is predominantly a consequence of the carbon-rich sediments these organisms precipitated.

Prior to this evolutionary development, our findings indicate that carbon emissions originating from mid-ocean ridges and continental rifts—regions where tectonic plates diverge—were, in fact, significantly more influential in contributing to atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

A Novel Perspective for Future Climate Appraisals

The insights derived from our research furnish a novel framework for understanding how Earth’s tectonic processes have historically shaped, and will continue to influence, our planet’s climate.

These findings suggest that Earth’s climatic equilibrium is not solely governed by atmospheric carbon concentrations. Rather, climate is intricately influenced by the delicate balance between carbon released from the Earth’s crust and its subsequent entrapment within oceanic sediments.

Furthermore, this study offers critical data for the advancement of future climate projections, particularly in light of prevailing concerns surrounding escalating carbon dioxide levels.

We now possess a clearer comprehension that Earth’s inherent carbon cycle, dynamically shaped by the subterranean migration of tectonic plates, plays a pivotal role in regulating planetary temperature.

This deep-time perspective can serve to enhance our predictive capabilities regarding future climatic trajectories and the ongoing ramifications of anthropogenic endeavors.

![]()