A decade has elapsed since Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 vanished from radar on March 8, 2014, cementing its status as one of aviation’s most confounding global enigmas.

The notion that a contemporary Boeing 777-200ER aircraft, carrying 239 souls, could simply cease to exist without any definitive explanation is profoundly disquieting. Nevertheless, despite extensive investigations spanning the past ten years, the primary wreckage and the remains of the passengers remain unrecovered.

During a recent commemoration, the Malaysian Minister of Transport disclosed plans for a renewed initiative to locate the aircraft.

Should this proposal receive endorsement from the Malaysian government, the maritime survey will be undertaken by Ocean Infinity, a seabed exploration company based in the United States, which previously conducted an unsuccessful search in 2018.

What transpired with MH370?

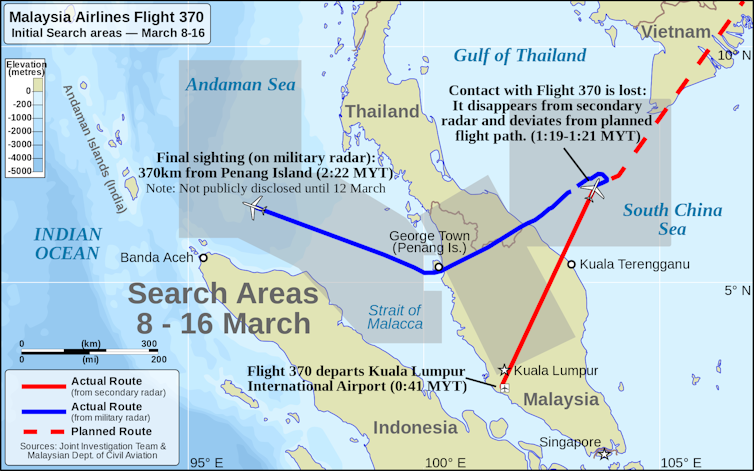

The flight’s intended route was from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing. Air traffic control lost communication with the aircraft approximately 60 minutes into its journey, over the South China Sea.

Subsequently, military radar tracked the plane as it traversed the Malay Peninsula, with its last recorded radar position being over the Andaman Sea, in the northeastern expanse of the Indian Ocean.

Following this, automated satellite communications exchanged between the aircraft and a British firm’s Inmarsat telecommunications satellite indicated that the aircraft had ultimately veered into the southeastern Indian Ocean, precisely along the 7th arc (defined as a series of geographical coordinates).

This data served as the foundation for establishing the preliminary search areas by the Australian Air Transport Safety Bureau. Initial aerial searches were concentrated in the South China Sea and the Andaman Sea.

To this day, the precise factors precipitating the aircraft’s diversion and subsequent disappearance remain unknown.

What are the findings from MH370 searches to date?

On March 18, 2014, a mere ten days subsequent to MH370’s vanishing, a search operation commenced in the southern Indian Ocean, spearheaded by Australia, with aerial contributions from multiple nations. This extensive search, which spanned until April 28, encompassed a vast oceanic area of 4,500,000 square kilometres. No discernible wreckage was discovered.

Furthermore, two distinct underwater search expeditions in the Indian Ocean, situated approximately 2,800 km to the west of Western Australia, have also failed to yield any conclusive evidence of the primary crash site.

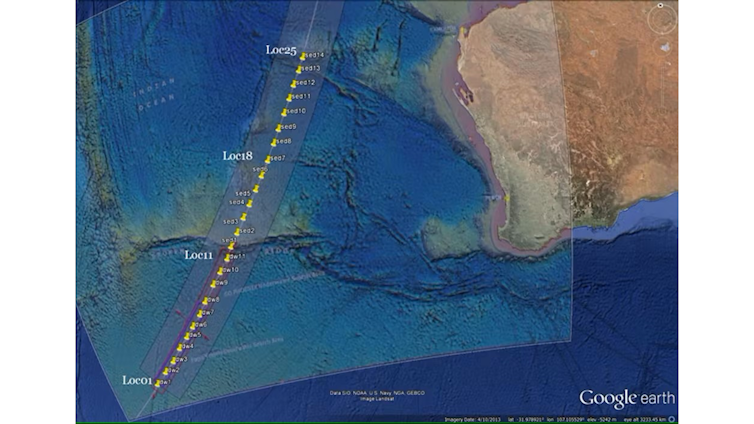

The initial seabed exploration effort, coordinated by Australia, covered an immense tract of 120,000 square kilometres, extending 50 nautical miles along the 7th arc. This meticulous undertaking, lasting 1,046 days, was suspended on January 17, 2017.

A subsequent search conducted by Ocean Infinity in 2018 surveyed an area exceeding 112,000 square kilometres. Although completed in just over three months, this operation also proved unsuccessful in locating the aircraft’s wreckage.

What about recovered debris?

While the principal crash location remains elusive, a number of scattered aircraft components have been discovered washing ashore in the intervening years since the flight’s disappearance.

Compellingly, in June 2015, officials from the Australian Air Transport Safety Bureau posited that debris might potentially reach Sumatra, a scenario appearing counterintuitive given the prevailing ocean currents of the region.

The most significant current in the Indian Ocean is the South Equatorial Current. Its eastward to westward flow, situated between northern Australia and Madagascar, would theoretically permit the drift of debris.

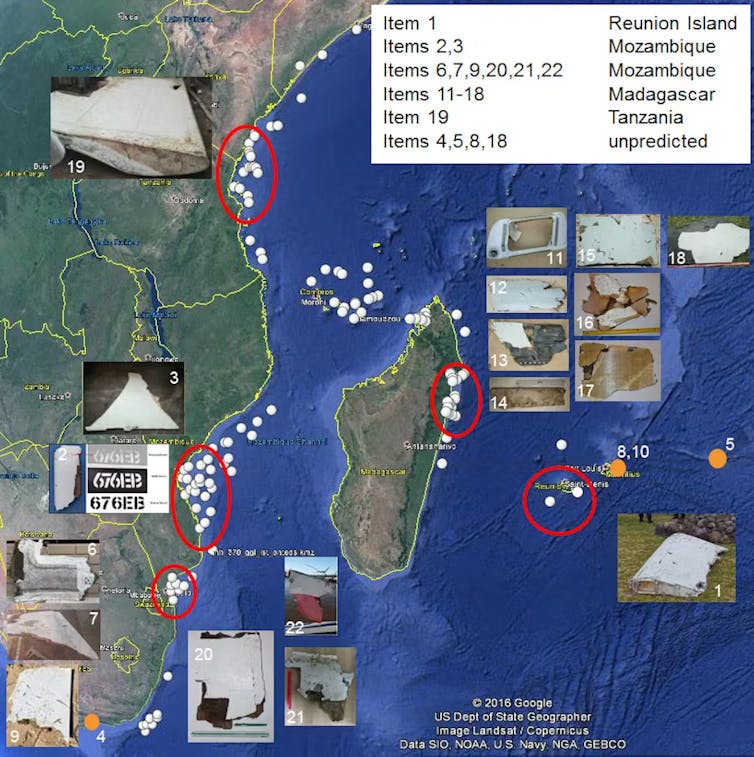

Indeed, on July 30, 2015, a substantial piece of wreckage—a flaperon (a movable segment of an aircraft’s wing)—was discovered on Reunion Island, located in the western Indian Ocean. Subsequent confirmation established its derivation from MH370.

A full twelve months prior, utilizing an oceanic drift simulation model, our research team at the University of Western Australia (UWA) had forecasted that any debris originating from the 7th arc would inevitably drift towards the western Indian Ocean.

In the subsequent months, additional fragments of aircraft debris were identified along the western Indian Ocean coastline in locations such as Mauritius, Tanzania, Rodrigues, Madagascar, Mozambique, and South Africa.

The drift analysis conducted by UWA accurately predicted the coastal landing sites for floating debris originating from MH370 in the western Indian Ocean. This predictive capability also guided the efforts of American explorer Blaine Gibson and others in the direct recovery of several dozen pieces of wreckage, three of which have been definitively identified as belonging to MH370, with several more considered highly probable.

To date, these recovered debris items from the western Indian Ocean constitute the sole physical evidence linked to MH370.

Furthermore, this evidence provides independent corroboration that the aircraft’s final resting place was in proximity to the 7th arc, as any floating debris would initially travel northward before being carried westward by the prevailing oceanic currents. These findings align with the conclusions of other drift studies conducted by independent researchers globally.

What is the rationale for a new MH370 search?

Regrettably, the oceanic environment is inherently unpredictable, and even sophisticated drift models are incapable of pinpointing the precise location of a crash site.

The proposed renewed search by Ocean Infinity has significantly refined the target search area to lie between latitudes 36°S and 33°S. This region is approximately 50 km south of the locations where UWA modelling predicted debris release along the 7th arc. Should the initial search prove unfruitful, its parameters could be extended northward.

Technological advancements have been substantial since the initial underwater search operations. Ocean Infinity is employing a fleet of autonomous underwater vehicles equipped with enhanced resolution capabilities. The forthcoming search will also utilize remotely operated surface vessels.

The designated search zone is characterized by oceanic depths of approximately 4,000 metres. Water temperatures in this area range from 1–2°C, with minimal currents. These environmental conditions suggest a high likelihood that, even after a decade, any debris field would remain relatively intact.

Consequently, there exists a significant probability that the aircraft’s wreckage can still be located. A successful future search would not only provide a measure of closure for the families of those lost but also for the thousands of individuals who have dedicated themselves to the ongoing search efforts.![]()