Within typically nutrient-depleted abyssal plains, the discovery of deceased cetacean remains establishes oases of sustenance, capable of supporting entire ecological communities for extended durations, particularly with the assistance of specialized bone-consuming polychaetes known as “zombie worms.”

However, recent scientific observations have indicated a conspicuous absence of these particular annelids (genus Osedax) in the vicinity of British Columbia’s coastline, at a profound oceanic depth of approximately 900 meters (3,000 feet) within the Pacific Ocean.

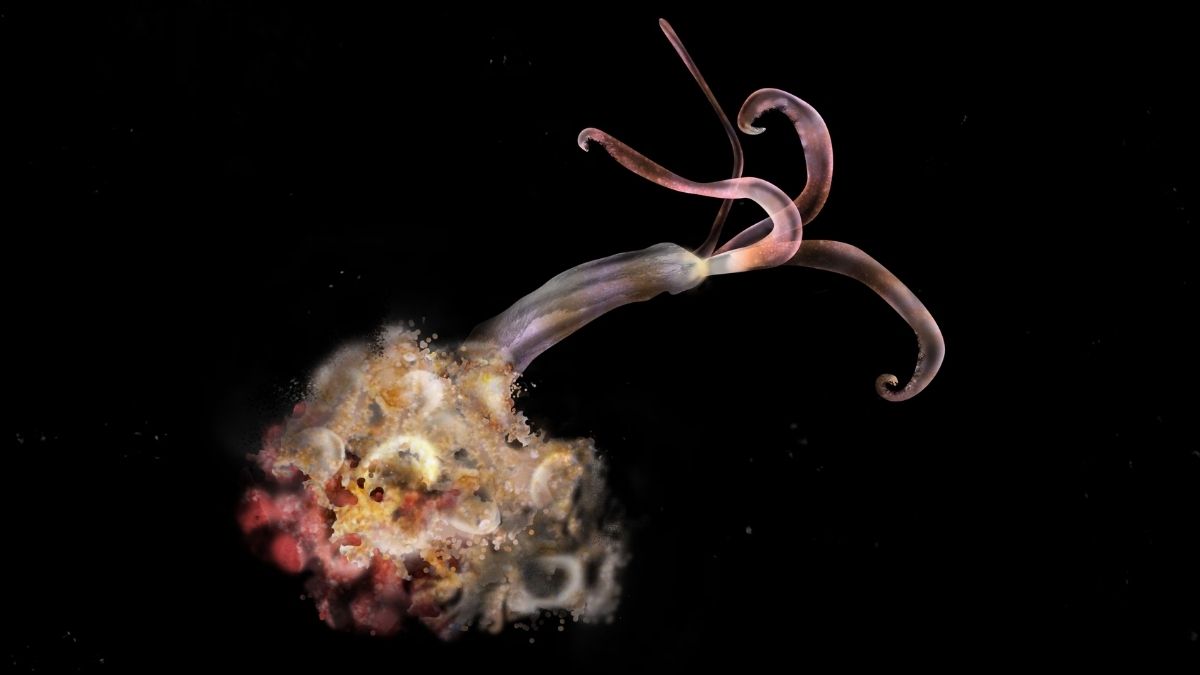

Under typical oceanic conditions, the larval stages of these worms drift freely in the water column, awaiting an opportune moment to affix themselves to recently deceased whale skeletons or other skeletal structures. Upon settlement, they rapidly attain maturity and initiate the secretion of an acidic compound from their root-like appendages, enabling them to penetrate the dense cortical layer of bone.

Each individual zombie worm harbors a symbiotic bacterial consortium within its physiology, which facilitates the assimilation of otherwise indigestible lipids and proteins, most notably collagen, derived from the skeletal material.

This protracted process of nutrient extraction liberates vital sustenance for a variety of deep-sea fauna, thereby enhancing the biodiversity and intricate network of relationships within these “whale fall” ecosystems. These unique microhabitats, upon their formation, serve as crucial migratory corridors or “stepping-stones” for species to traverse vast oceanic distances, spanning hundreds of kilometers.

It is therefore a cause for significant concern that, despite the deployment of humpback whale bones on the deep seafloor off the coast of British Columbia, sophisticated monitoring equipment revealed no trace of zombie worms over a continuous 10-year observation period.

The research collective responsible for this investigation, spearheaded by benthic ecologist Fabio De Leo of the University of Victoria, posits that a deficiency in dissolved oxygen may be the primary factor contributing to the worms’ dormancy.

The area designated as Barkley Canyon, where the whale bones were situated and scrutinized, is characterized by naturally low oxygen concentrations. However, regions of the deep ocean experiencing such hypoxic or anoxic conditions – commonly referred to as oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) or ‘dead zones’ – are undergoing an expansion attributed to the impacts of climate change.

“Fundamentally, we are contemplating the possibility of species extirpation,” stated De Leo.

“It appears that the proliferation of OMZs, a direct consequence of elevated ocean temperatures, portends unfavorable outcomes for these remarkable ecosystems sustained by whale and wood falls along the northeastern Pacific Margin,” commented Craig Smith, an oceanographer from the University of Hawai’i who co-directed the research initiative alongside De Leo.

Smith and De Leo are currently monitoring an additional whale carcass located at the Clayoquot Slope, offshore from Vancouver Island. This ongoing observation is anticipated to yield further crucial insights into the potential decline of zombie worm populations in our global oceans.

The foundational research underpinning these findings was disseminated in the peer-reviewed journal Frontiers in Marine Science in the year 2024.