Envision yourself as a copper extraction specialist in southeastern Europe during the year 3900 BCE. Each day is consumed by the arduous task of moving copper ore through the mine’s oppressive tunnels.

You had come to accept the relentless drudgery of subterranean life. Then, one afternoon, you observe a fellow laborer performing an extraordinary feat.

Employing a peculiar apparatus, he effortlessly conveys a load equivalent to thrice his own body mass in a single excursion. As he returns to the excavation to retrieve another consignment, the realization strikes you: your chosen occupation is poised for a significant reduction in toil and a substantial increase in financial reward.

What remains unknown to you is that you are witnessing an event destined to reshape the trajectory of civilization—not merely for your isolated mining enclave, but for the entirety of humankind.

Notwithstanding the wheel’s profound and immeasurable influence, its precise inventor, along with the time and location of its initial conceptualization, remain subjects of uncertainty. The hypothetical scenario detailed above is posited by a 2015 theory suggesting that miners in the Carpathian Mountains—situated in contemporary Hungary—were the progenitors of the wheel, nearly 6,000 years ago, as a mechanism for transporting copper ore.

This hypothesis is bolstered by the archaeological discovery of over 150 diminutive wagon replicas by excavators in the vicinity. These petite, four-wheeled models were fabricated from clay, and their exterior surfaces bore incised patterns resembling wickerwork, evocative of the basketry employed by mining communities of that era.

Subsequent radiometric dating has confirmed that these wagons represent the earliest known representations of wheeled conveyance discovered to date.

This theory also brings forth a query of particular fascination for myself, an aerospace engineer engaged in the study of engineering design principles. How did a reclusive, scientifically unsophisticated mining society arrive at the innovation of the wheel, while profoundly advanced civilizations, such as ancient Egypt, failed to do so?

A Contentious Postulation

The prevailing assumption has long been that wheels originated from rudimentary wooden cylinders. However, until recently, a clear explanation for the mechanism and impetus behind this metamorphosis was absent. Furthermore, commencing in the 1960s, a contingent of researchers began to articulate significant reservations regarding the roller-to-wheel developmental pathway.

Indeed, for cylindrical rollers to prove efficacious, they necessitate uniformly level, firm ground and unobstructed transit routes free from gradients and sharp turns. Moreover, once the conveyance has passed, the expended rollers must be continuously repositioned to the forefront of the process to sustain the cargo’s momentum.

Consequently, in antiquity, rollers saw limited and sporadic application. According to the skeptics, rollers were too uncommon and impractical to have served as the foundational element in the wheel’s evolutionary sequence.

However, a mining environment, characterized by its enclosed, man-made passages, would have furnished advantageous conditions for the utilization of rollers. This specific factor, among others, motivated our research team to re-examine the roller hypothesis.

A Pivotal Juncture

The transition from rollers to wheels necessitates the integration of two pivotal advancements. The initial advancement pertains to the modification of the cart employed for cargo transport. The base of the cart must be equipped with concave receptacles designed to securely house the rollers. In this manner, as the operator propels the cart, the rollers remain engaged and move in synchrony with it.

This particular innovation may have been spurred by the restricted confines of the mining setting, where the continuous necessity of transporting used rollers back to the cart’s front would have presented a particularly burdensome task.

The advent of socketed rollers marked a critical turning point in the wheel’s developmental trajectory, thereby paving the way for the subsequent and most significant innovation.

This next evolutionary phase involved a fundamental alteration to the rollers themselves. To comprehend the rationale and methodology behind this modification, we drew upon principles of physics and computational engineering.

Simulating the Wheel’s Evolutionary Path

To initiate our inquiry, we developed a computational program engineered to simulate the evolutionary process from a roller to a wheel. Our central hypothesis proposed that this metamorphosis was primarily driven by a principle known as “mechanical advantage.”

This identical principle is what empowers tools like pliers to amplify a user’s gripping force by providing augmented leverage. Analogously, if the contour of a roller could be refined to generate mechanical advantage, this would amplify the operator’s propulsive force, thereby facilitating the cart’s forward motion.

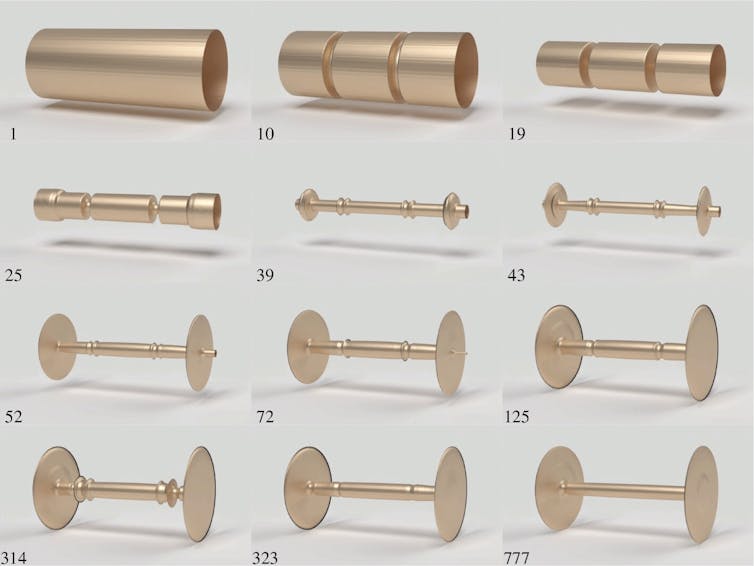

Our algorithmic approach involved modeling hundreds of prospective roller configurations and meticulously assessing their performance metrics, encompassing both mechanical advantage and structural integrity.

The latter parameter was implemented to ascertain whether a specific roller design would withstand the imposed load of the cargo without catastrophic failure. As anticipated, the algorithm ultimately converged upon the familiar wheel-and-axle configuration, which it identified as the optimal solution.

Throughout the algorithm’s execution, each successive iteration of a design exhibited incremental improvements over its predecessor. We posit that a comparable evolutionary cascade transpired among the miners approximately 6,000 years ago.

The initial catalyst prompting the miners to explore alternative roller configurations remains a subject of conjecture. One plausible explanation is that frictional wear at the roller-socket interface led to the gradual erosion of the surrounding wood, resulting in a subtle reduction in the roller’s diameter at the point of contact.

Another conjecture posits that the miners began to decrease the thickness of the rollers to enable their carts to traverse minor impediments on the subterranean terrain.

Regardless of the specific impetus, the refinement of the axle region, facilitated by mechanical advantage, rendered the carts more facile to propel. As time elapsed, superior-performing designs were consistently favored, and new rollers were meticulously crafted to replicate these exemplary models.

Consequently, the rollers progressively diminished in width, culminating in a configuration where only a slender bar remained, capped at each extremity by substantial discs. This rudimentary assembly signifies the genesis of what we now designate as “the wheel.”

According to our theoretical framework, the wheel’s invention was not a singular, discrete event. Rather, akin to biological evolution, the wheel emerged incrementally through the cumulative effect of minor enhancements.

This represents but one of the myriad chapters in the wheel’s extensive and ongoing evolutionary narrative. Over 5,000 years subsequent to the contributions of the Carpathian miners, a Parisian bicycle artisan devised radial ball bearings, an innovation that once again profoundly transformed wheeled transportation.

Ironically, ball bearings are conceptually analogous to rollers, the wheel’s evolutionary antecedent. Ball bearings form a circular interface around the axle, establishing a rolling contact between the axle and the wheel’s hub, thereby mitigating friction. With this singular advancement, the wheel’s evolutionary journey has effectively completed a full circuit.

This illustration further underscores how the wheel’s developmental trajectory, mirroring its iconic circular form, follows an intricate and circuitous path—one devoid of a definitive origin or conclusion, marked by countless silent transformations along its continuum.

![]()