A pervasive parasite residing permanently within the cerebral regions of millions might exhibit a less uniformly quiescent state than previously hypothesized by scientific consensus.

Investigators affiliated with the University of California, Riverside (UCR) have recently unearthed compelling evidence indicating low-level T. gondii recrudescence within the murine encephalon, even throughout prolonged periods of infestation.

Currently, upwards of one-third of the global human populace harbors infection by Toxoplasma gondii, a cerebral-invasive protozoan that achieves reproductive maturity in feline hosts, with rodents and various other fauna serving as intermediary carriers.

While this pathogen frequently infiltrates healthy human subjects, typically through inadvertent exposure to feline excrement or undercooked meats, resultant infections generally manifest with negligible symptomatology, leaving the majority of sufferers oblivious to their parasitic burden.

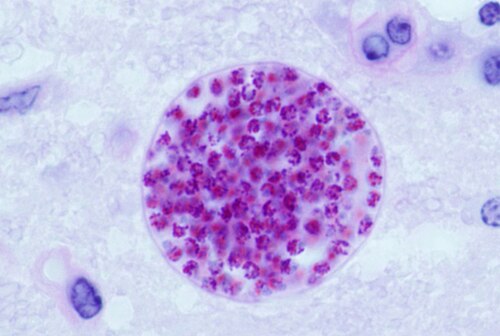

Unbeknownst to the host organism, the protozoan establishes parasitic cysts within the neural, cardiac, and muscular tissues, where it may persist for an entire lifespan – seemingly inert until the host’s immunological defenses begin to wane.

However, it appears that subterranean activity is occurring within these encapsulations.

Up to this juncture, prevailing scientific dogma presumed that each minute cyst housed a solitary archetypal form of T. gondii in a dormant state. Nevertheless, UCR researchers have employed single-cell RNA sequencing techniques to delineate the presence of multiple distinct subtypes cohabiting within the brains of their experimental subjects.

“We have ascertained that the cyst is not merely a passive refuge; rather, it operates as a dynamic nexus, accommodating diverse parasitic morphologies optimized for survival, propagation, or resurgence,” elucidates Emma Wilson, a biomedical researcher at UCR.

“Our findings fundamentally alter our perception of the Toxoplasma cyst,” she further remarked. “It recontextualizes the cyst as the central regulatory locus of the parasite’s life cycle, thereby illuminating critical targets for novel therapeutic interventions. To effectively manage toxoplasmosis, the cyst represents the paramount area of investigational focus.”

Toxoplasmosis denotes a pathological condition in humans instigated by T. gondii, which can precipitate an influenza-like illness accompanied by psychological sequelae. It predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals, occasionally precipitating convulsive episodes or visual impairments.

While antiparasitic pharmacotherapy can offer amelioration, addressing the acute manifestation and the latent parasitic state necessitates distinct medicinal agents.

“By pinpointing disparate parasitic subpopulations within cysts, our investigation precisely identifies those subtypes most predisposed to reactivation and subsequent pathogenesis,” states Wilson.

“This insight elucidates the challenges encountered in prior drug development endeavors and suggests novel, more specific therapeutic targets for future pharmaceutical design.”

Within the cerebral tissues of murine subjects subjected to chronic T. gondii infection (spanning 28 days), Wilson and her research collaborators observed that cysts harbored a greater heterogeneity of parasitic subtypes compared to the acute phase of infestation.

During the initial week or so post-infection, the parasites appeared to transition into a more rapid proliferative phase, subsequently shifting to a slower-growing modality and forms conducive to cyst maintenance.

The authors posit that a linear, sequential developmental trajectory is improbable, implying that our current understanding of this parasitic affliction requires substantial revision.

“For numerous decades, the Toxoplasma life cycle has been conceptualized through an excessively simplified paradigm,” affirms Wilson. “Our research critically challenges that established model.”

The findings of this investigation have been formally disseminated in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications.