A novel giant virus, identified by researchers in Japan, is providing unprecedented insights into this peculiar class of viruses and potentially shedding light on the origins of complex, multicellular life forms.

This newly identified virus was detected within an amoeba inhabiting a freshwater body located near Tokyo, as reported by the investigative team. The organism has been christened “ushikuvirus,” deriving its name from Ushiku-numa, the specific pond where it was found in Ibaraki Prefecture.

Giant viruses were largely disregarded throughout the initial century of contemporary virology. Early discoveries were frequently misclassified as bacteria owing to their substantial size. Although their existence was barely acknowledged until recent decades, it is now understood that giant viruses are pervasive in our environment.

Collectively, viruses are recognized as the most prevalent biological entities on our planet and among the most enigmatic. Significant gaps persist in our understanding of viral evolutionary trajectories, and there remains a debate regarding their classification as living organisms.

Regardless of their ontological status—whether living or not—viruses undeniably exert a profound influence on all life forms, including humanity. This influence extends beyond simply commandeering host cells to induce pathology; it also involves occasional manipulation of a host’s evolutionary trajectory.

Viruses possess the capacity to facilitate horizontal gene transfer between organisms. Certain types, known as retroviruses, integrate their genetic material into the host cell’s genome. Should this integration occur within the germline cells, the viral DNA can be transmitted to subsequent generations.

Indeed, ancient retroviral remnants constitute up to 8 percent of the human genome, and these remnants have conferred advantages. Retroviral DNA may have endowed early vertebrates with the capacity to produce myelin and played a crucial role in the development of the placenta.

Considerably further back in evolutionary history, viruses might have been instrumental in initiating an even more significant and mysterious advancement: the evolutionary transition from prokaryotes, or single-celled organisms, to eukaryotes, or multicellular organisms.

Eukaryotic cells characteristically possess a membrane-bound nucleus, signifying a fundamental “chasm in design” when compared to their prokaryotic predecessors, which lacked such a structure. The precise mechanism by which this dramatic transformation occurred remains unclear, yet a compelling hypothesis suggests that the nucleus originated as a contribution from viruses.

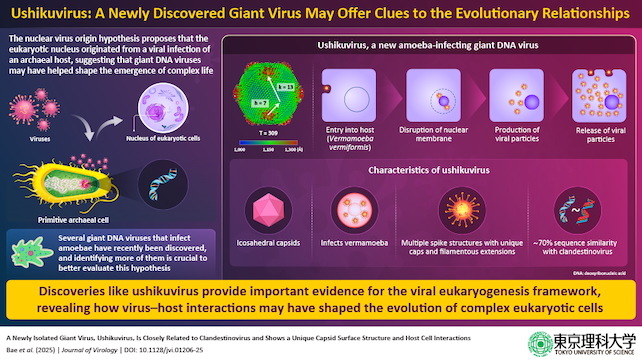

This concept, termed viral eukaryogenesis, was initially articulated in 2001 by Masaharu Takemura, a molecular biologist affiliated with the Tokyo University of Science. His proposal posited that the nucleus of eukaryotic cells evolved from a large DNA virus, akin to a poxvirus, which infected a primordial prokaryote.

Rather than inducing harm, the virus integrated itself into the cell’s cytoplasm, ultimately acquiring essential genetic material from its host and undergoing a gradual transformation into a cellular nucleus.

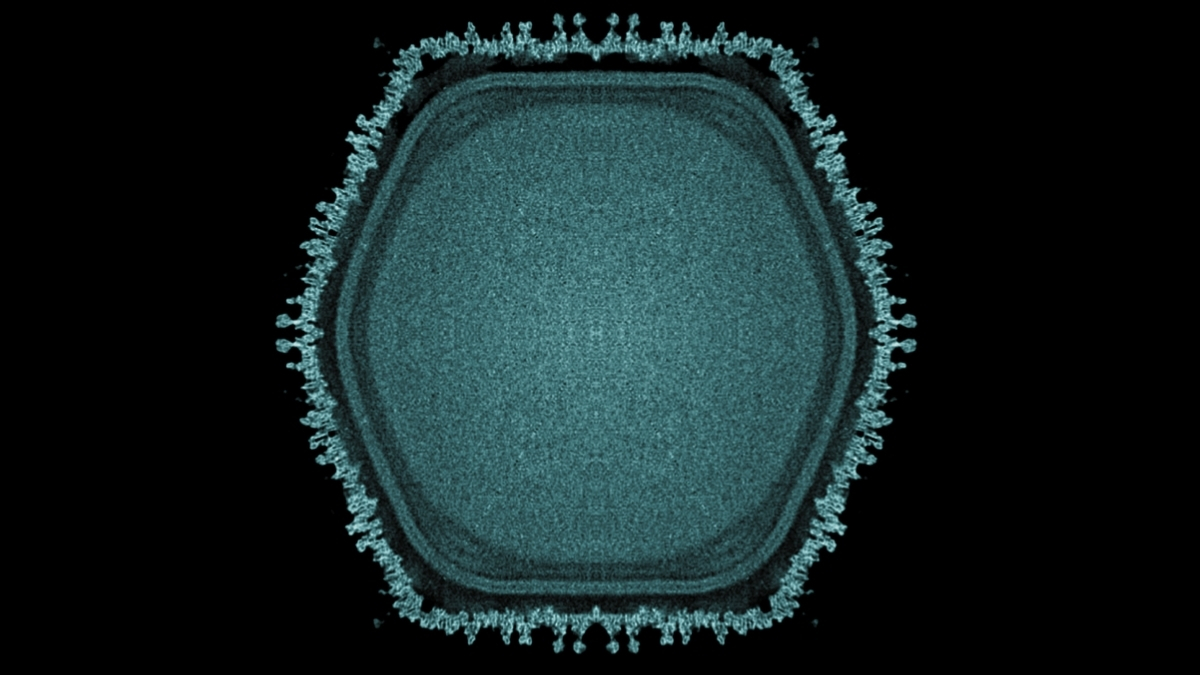

This hypothesis gained considerable support following the 2003 discovery of giant viruses containing DNA. These viruses were observed to fabricate structures known as “virus factories” within their host cells. These factories are occasionally encased in a membrane and exhibit functional and structural similarities to the nuclei found in eukaryotic cells.

Since then, a variety of these giant viruses have been identified, including species belonging to the Mamonoviridae family and the closely related clandestinovirus, both of which infect specific amoeba species. The considerable diversity and isolation challenges associated with giant viruses make a new discovery like ushikuvirus a significant event.

Takemura continues his research into viral eukaryogenesis, a quarter-century after first introducing the concept, and was a participant in the research team responsible for the identification and characterization of ushikuvirus in the recent study.

“Giant viruses can be considered a reservoir of knowledge whose full extent remains to be elucidated,” Takemura states. “A future implication of this research could be to offer humanity a novel perspective that bridges the macroscopic world of living organisms with the microscopic realm of viruses.”

Ushikuvirus infects amoebae of the genus Vermamoeba (Vermamoeba vermiformis), a characteristic it shares with clandestinovirus. Furthermore, its morphology and the spiky exterior of its capsid bear a resemblance to those of medusaviruses.

However, it also presents distinctions from other giant viruses. For instance, it compels its host cells to undergo abnormal enlargement, and the spikes on its capsid feature unique tips and fibrous formations.

Contrary to the practice of preserving a host cell’s nucleus and replicating within it, as observed with clandestinovirus and medusaviruses, ushikuvirus instead establishes a viral factory and disrupts the host’s nuclear membrane.

These shared traits and notable differences serve as critical indicators, aiding scientists in reconstructing the evolutionary history of giant viruses. Takemura and his colleagues aim to ascertain the mechanisms and reasons behind their substantial diversification, as well as their specific contributions to the emergence of eukaryotes like ourselves.

“The discovery of a novel virus related to Mamonoviridae, termed ‘ushikuvirus,’ which exhibits a different host preference, is anticipated to enhance our understanding and foster discussions concerning the evolution and phylogeny of the Mamonoviridae family,” Takemura observes.

“Consequently, it is believed that we will gain a deeper insight into the enigmas surrounding the evolution of eukaryotic organisms and the mysteries inherent in giant viruses,” he concludes.