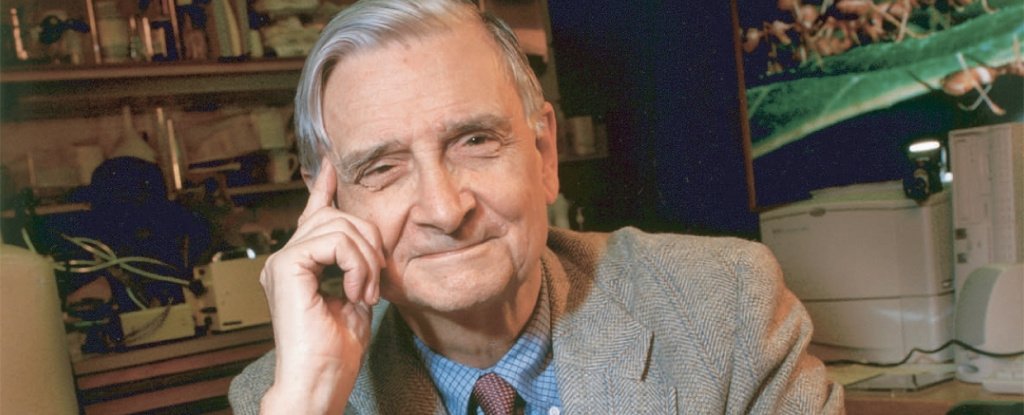

E. O. Wilson was, by all accounts, an exceptional intellect and a towering figure in academia. I vividly recall a conversation in the 1980s with Milton Stetson, who then chaired the biology department at the University of Delaware. He shared his perspective that a scientist achieving even a single, groundbreaking contribution to their discipline should be considered remarkably successful.

By the time I had the privilege of meeting Edward O. Wilson in 1982, his scientific legacy already boasted at least five such paradigm-shifting advancements.

Wilson, who passed away on December 26, 2021, at the age of 92, was instrumental in deciphering the chemical language used by ants for communication.

Furthermore, he elucidated the critical role that habitat size and its geographical placement play in maintaining the viability of animal populations.

His pioneering work also led him to be the first to comprehend the evolutionary underpinnings governing both animal and human social structures.

Each of these seminal contributions irrevocably altered the investigative approaches within their respective scientific domains, offering a clear explanation as to why E. O. – as he was affectionately known – was revered as an academic luminary by countless aspiring scientists, myself included.

This extraordinary catalog of accomplishments can likely be attributed to his remarkable aptitude for synthesizing novel concepts by drawing upon insights from diverse academic fields.

Profound Discoveries from Humble Subjects

In 1982, during a respite at a specialized conference focused on social insects, I found myself seated near the esteemed scientist. He turned, offered a handshake, and introduced himself, “Hi, I’m Ed Wilson. I don’t believe we’ve met.” Our ensuing conversation continued until it was time to resume the conference proceedings.

A mere three hours later, I approached him once more, this time with considerably less apprehension, confident that we had by then forged a strong acquaintance. He turned, extended his hand, and again offered, “Hi, I’m Ed Wilson. I don’t believe we’ve met.”

Wilson’s apparent recollection lapse, coupled with his continued warmth and genuine interest, revealed a deeply human and compassionate individual beneath his multifaceted brilliance. As a recent graduate, it’s highly probable that no one else at that gathering possessed less knowledge than I did – a fact that Wilson, I am certain, recognized the moment I began to speak. Nevertheless, he readily engaged with me, not just on one occasion, but twice.

Fast forward thirty-two years to 2014, and our paths crossed again. I had received an invitation to participate in a ceremony commemorating his reception of the Franklin Institute’s prestigious Benjamin Franklin Medal for Earth and Environmental Science. This accolade celebrated Wilson’s lifelong scientific contributions, with particular emphasis on his extensive endeavors to safeguard Earth’s lifeforms.

My own research, which involves investigating native flora and fauna and their indispensable role in food webs, was profoundly influenced by Wilson’s eloquent expositions on biodiversity and the intricate web of interspecies relationships that underpin the very existence of these organisms.

For the initial decades of my professional journey, I focused on the evolutionary aspects of insect parental care. Wilson’s early publications provided a wealth of testable hypotheses that effectively guided this research. However, it was his seminal 1992 book, The Diversity of Life, that deeply resonated with me, ultimately serving as the catalyst for a significant pivot in my career trajectory.

Despite my specialization as an entomologist, I had not fully grasped the profound importance of insects as the “little things that run the world” until Wilson eloquently articulated this concept in 1987. Like a vast majority of both scientific and general audiences, my comprehension of how human well-being is sustained by biodiversity was regrettably superficial. Fortunately, Wilson succeeded in broadening our collective perspective.

Throughout his distinguished career, Wilson staunchly refuted the prevailing academic sentiment that natural history – the observational study of the natural world rather than experimental investigation – lacked significance. He proudly identified himself as a naturalist and consistently emphasized the critical imperative to study and preserve the natural world.

Long before it gained mainstream recognition, he astutely recognized that our collective failure to acknowledge planetary limitations, combined with the inherent unsustainability of perpetual economic expansion, was propelling humanity toward an ecological precipice.

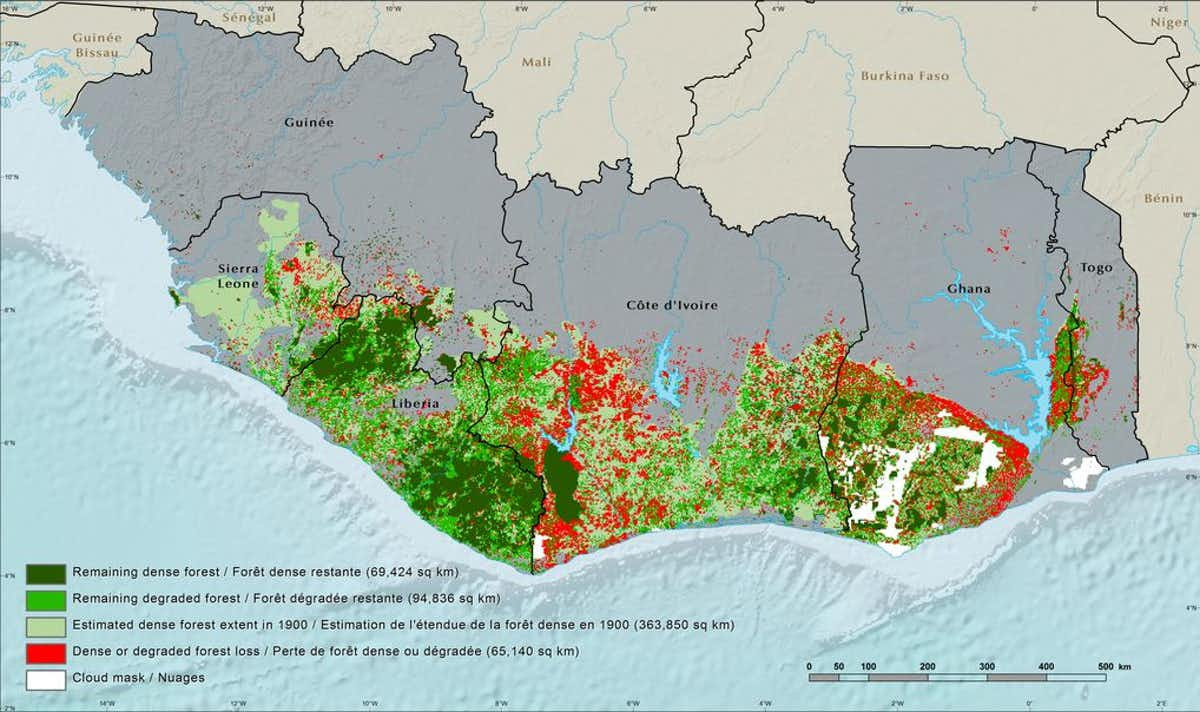

Depiction of deforestation in West Africa’s Upper Guinean Forest between 1975 and 2013. (Source: USGS)

Depiction of deforestation in West Africa’s Upper Guinean Forest between 1975 and 2013. (Source: USGS)

Wilson understood that humanity’s detrimental impact on the very ecosystems that sustain us was not only a precursor to our own downfall but was also precipitating the sixth mass extinction event in Earth’s history, and alarmingly, the first one instigated by a species – ourselves. This catastrophic decline threatened the biodiversity he so deeply cherished, forcing it toward the brink of irreversible loss.

A Comprehensive Vision for Environmental Stewardship

Thus, to his lifelong fascination with ants, E. O. Wilson passionately added a second profound commitment: the urgent need to guide humanity towards a more sustainable mode of existence.

To achieve this monumental objective, he recognized the necessity of transcending academic ivory towers and communicating his message to the general public, understanding that a single publication would be insufficient. Genuine learning necessitates repeated exposure to ideas, and this is precisely what Wilson delivered across his prolific body of work, including The Diversity of Life, Biophilia, The Future of Life, The Creation, and his final, impassioned call to action in 2016, Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life.

As Wilson entered his later years, his writings became imbued with an increasing sense of urgency, superseding any adherence to political correctness. He courageously exposed the ecological devastation wrought by dogmatic religious ideologies and unchecked population growth, while simultaneously challenging the foundational tenets of conservation biology, asserting that effective conservation could not be achieved by confining efforts to diminutive, isolated ecological fragments.

Within the pages of Half Earth, he synthesized a lifetime of ecological wisdom into a singular, albeit ambitious, principle: the continued existence of life as we know it is contingent upon the preservation of functioning ecosystems across at least half of the Earth’s surface.

However, the feasibility of this ambitious directive is a matter of considerable debate. A significant portion of the planet is currently dedicated to various forms of agriculture, and the remaining half is densely populated by 7.9 billion people and their extensive infrastructural networks.

From my perspective, the sole viable pathway to realizing E. O.’s lifelong aspiration lies in our collective ability to cultivate a harmonious symbiotic relationship with the natural world, coexisting within the same spaces and at the same time. It is imperative that we decisively abandon the outdated notion that humanity occupies a separate realm from nature. For the past two decades, my principal objective has been to furnish a comprehensive framework for this radical cultural paradigm shift, and I am deeply honored that this pursuit aligns so perfectly with E. O. Wilson’s profound vision.

In this critical endeavor, there is no time to be lost. As Wilson himself aptly stated, “Conservation is a discipline with a deadline.” Ultimately, whether humanity possesses the collective wisdom to meet this impending deadline remains an open question. ![]()