In parallel with the pursuit of justice, scientific endeavor flourishes most effectively when unclouded by prejudice. For approximately two hundred years, this principle has served as the bedrock of sound experimental methodology.

The practice of obscuring observations that carry the potential to introduce bias has long been established as a benchmark for research reliability. However, a consortium of UK-based scientists has posited that in numerous scenarios, this practice may represent an inefficient expenditure of resources, potentially yielding adverse outcomes.

Clinical researcher Rohan Anand from Queen’s University Belfast, in conjunction with collaborators from the University of Edinburgh and the Centre for Public Health in Belfast, asserts that researchers should engage in profound deliberation prior to incorporating blinding protocols into their experimental designs.

Their core contention revolves around a cost-benefit evaluation. While the potential advantages of a blinded trial are readily acknowledged, certain less apparent ramifications might render the undertaking disproportionate to the perceived benefits.

“Given the upward trajectory in the number of new trials, with over 25,000 registered since the commencement of 2019, we harbor concerns that a significant allocation of temporal, energetic, and financial resources may be directed towards the consideration and implementation of blinding without a substantiated justification for its necessity,” state Anand and his co-authors in a recent Analysis piece published in The BMJ.

The existence of this ‘substantiated’ justification is frequently taken for granted. After all, science developed as a system of checks and balances designed to ensure that our most cherished hypotheses about the universe were not mere flights of fancy, born from social pressure or wishful thinking.

Alongside the principles of experimental replication, the utilization of positive and negative controls, statistical significance testing, and the random assignment of participants, employing observers who are unaware of experimental conditions stands as another mechanism for safeguarding against the conflation of imagination with validated reasoning.

However, none of these safeguards are without their associated expenses. For instance, the recruitment and preliminary assessment of participants represent a considerable undertaking, a fact well-known to anyone who has navigated postgraduate research. Furthermore, participant retention throughout the entire study period is not always guaranteed.

When evaluating novel pharmaceutical agents, these challenges can become particularly acute.

“The principal reasons cited by patients for their reluctance to consent to participation in these trials included a preference for a specific named medication or a desire to know the precise composition of the administered tablets,” the researchers highlight.

If a quarter of your prospective participants voice reservations about the possibility of receiving a placebo instead of the active treatment, for example, the options are twofold: either recruit a larger cohort, thereby incurring additional time and resource demands, or accept the potential for an underpowered study.

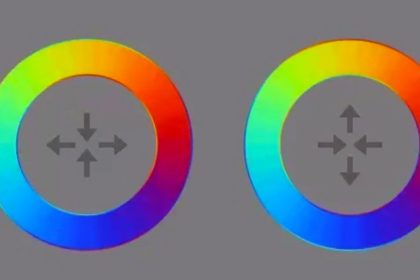

Even if a sufficient number of willing individuals are identified for study, the placebos must be crafted to be indistinguishable in appearance, texture, and even taste. In an ideal scenario, they would even mimic potential side effects to create a fully convincing illusory experience.

While the cost of a few inert pills might be negligible, as Anand and his associates articulate: “The financial investment in blinding mechanisms carries opportunity costs, potentially diverting funds that could otherwise be utilized to enhance critical aspects of trial robustness, such as the professional development of research personnel, the expansion of sample sizes, and the thorough assessment of outcomes.”

Consequently, while superior blinding might be achieved, if this came at the sacrifice of an adequate participant pool or realistic placebos, the overall effectiveness of the study could be compromised.

Beyond the financial implications, the blind evaluation of therapeutic interventions in clinical investigations introduces significant ethical quandaries, particularly when treatment moratoriums or modifications to existing care regimens are implemented.

The deliberate withholding of information from study participants, even with their explicit consent, can also present a moral quandary.

At best, this omission of detail may only subtly influence participant behavior, thereby compromising the validity of the data they provide.

For instance, obscuring pedagogical methodologies or novel instructional tools from students in an educational experiment, or concealing brand identities from potential consumers in a commercial setting, risks generating evidence that diverges from real-world conditions.

“The endeavor to minimize biases through blinding may diminish the capacity for accurate predictive modeling, as blinding protocols are unlikely to be employed in standard operational practices,” the research cadre elaborates.

This discourse is not intended to suggest that blinding is inherently a flawed technique.

Its notably auspicious origins, stemming from a royal commission investigating the efficacy of an 18th-century quack remedy, possess an almost legendary quality. If anything, its inception underscores its potency in ensuring that scientific inquiry remains impervious to the allure of popular trends.

However, there is a palpable risk of an overcorrection, particularly within the intensely competitive academic arena characterized by the ‘publish or perish’ imperative.

With a ceaseless volume of research vying for attention across myriad journals annually, the perfunctory application of blinding as a mere procedural checkbox, intended to confer an automatic veneer of rigor, could inadvertently undermine the very integrity of the scientific process.

“Double-blinded protocols are not invariably the optimal approach for obtaining a reliable answer to a trial’s central research question,” the investigators conclude.

The paramount strength of scientific inquiry, unequivocally, lies in its capacity to ascertain the validity of a proposition not merely through a checklist of criteria, but through a discerning comprehension of the historical discourse surrounding it.

Indeed, biases represent a pervasive challenge across the entire scientific landscape. As we progress, the domain of big data is gaining prominence as we seek solutions within extensive statistical repositories, employing algorithms purported to be ‘unbiased’—an assumption that can, in turn, serve to obscure deeply embedded prejudices within the underlying code.

Blinding will undoubtedly continue to serve as a potent instrument for demarcating verifiable facts from conjecture within the scientific realm for the foreseeable future, provided it does not come at the expense of the very methodologies that imbue science with its inherent trustworthiness.

This analytical review was featured in The BMJ.