A particular genetic alteration has been identified within the Rho GTPase Activating Protein 36 (Arhgap36) gene, and according to a consortium of researchers affiliated with the Stanford University School of Medicine, this specific mutation appears to be unique to domestic cats, with no known counterparts in other mammalian species.

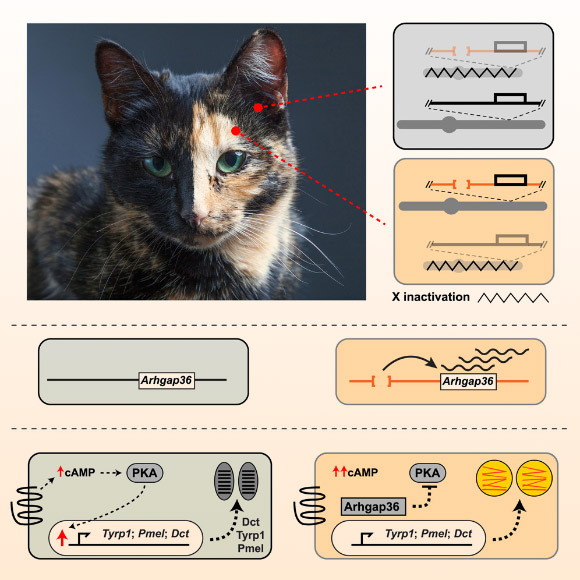

The sex-linked orange mutation in domestic cats is responsible for the variegated patches of reddish/yellow hair observed and serves as a definitive marker for the random X inactivation process in female tortoiseshell and calico cats. Notably, unlike the genetic basis for most coat color variations, the sex-linked orange trait lacks a discernible homolog in other mammalian species. The research conducted by Kaelin and associates indicates that this sex-linked orange coloration is attributable to a 5-kilobase deletion that results in the aberrant, melanocyte-specific expression of the Arhgap36 gene.

While numerous mammalian species exhibit orange or reddish hues—exemplified by tigers, golden retrievers, orangutans, and individuals with red hair—the linkage of orange coloration to sex, leading to its disproportionate prevalence in males, is a phenomenon exclusive to domestic felines (Felis silvestris catus).

“For a variety of species displaying yellow or ochre pigmentation, the genetic alterations responsible almost invariably involve one of two specific genes, neither of which is associated with sex linkage,” stated Dr. Christopher Kaelin, a distinguished researcher from the Stanford University School of Medicine and the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology.

Although scientific inquiry has successfully identified the common genetic modifications that prompt pigment cells in the skin to generate yellow or orange pigment rather than the standard brown or black, the precise location of the corresponding mutation in cats remained elusive until recently.

The observation that male orange cats are significantly more common provided a strong indication that this specific mutation, designated as sex-linked orange, resided on the X chromosome.

In the case of male felines, the presence of the sex-linked orange mutation results in a uniformly orange coat. However, for a female cat to possess a completely orange coat, she must inherit the sex-linked orange trait on both of her X chromosomes, a less probable genetic outcome.

Female cats carrying a single copy of the sex-linked orange mutation often exhibit a mottled pattern, known as tortoiseshell, or display distinct patches of orange, black, and white, characteristic of calico cats.

This differential expression is a consequence of a biological mechanism in females termed random X inactivation, wherein one of the two X chromosomes is rendered inactive within each somatic cell.

The outcome of this process is a mosaic of pigment cells, some of which express the sex-linked orange trait, while others do not.

“This represents a genetic anomaly that was first recognized over a century ago,” Dr. Kaelin remarked.

“It is precisely this comparative genetic enigma that fueled our fascination with the sex-linked orange phenomenon.”

Building upon earlier research that had begun to delineate the specific region of the X chromosome harboring the mutation, Dr. Kaelin and his research colleagues systematically homed in on the sex-linked orange trait through a meticulous, iterative investigation.

“Our capacity to undertake this research has been profoundly advanced by the development of comprehensive genomic resources for the domestic cat, which have become accessible within the last five to ten years,” Dr. Kaelin elaborated.

“These resources include the complete sequenced genomes from a diverse array of feline individuals.”

Furthermore, the investigative team procured DNA samples from cats undergoing spaying and neutering procedures.

Initially, the researchers scrutinized the X chromosome for genetic variations that were consistently present in male orange cats, identifying 51 potential candidates.

Subsequently, 48 of these candidates were discarded from further consideration, as they were also detected in some cats that did not exhibit orange coloration.

Among the remaining three variants, one particularly stood out due to its apparent involvement in gene regulation: a small deletion suspected to enhance the activity of an adjacent gene known as Arhgap36.

“At the juncture of its discovery, the Arhgap36 gene had no established association with pigmentation,” Dr. Kaelin commented.

This particular gene, which demonstrates a high degree of conservation across mammalian species, had been the subject of scientific inquiry within the fields of oncology and developmental biology.

Ordinarily, Arhgap36 is expressed in neuroendocrine tissues, where its overexpression can contribute to tumor formation. Its function within pigment cells was not previously understood.

However, Dr. Kaelin and his team made a groundbreaking discovery: its role in pigment cells is, in fact, significant, particularly in felines with orange coats.

“Arghap36 is not found to be expressed in the pigment cells of mice, humans, or even in the pigment cells of non-orange cats,” Dr. Kaelin clarified.

“The mutation observed in orange cats appears to trigger the expression of Arhgap36 within a specific cell type—the melanocyte—where it is not typically active.”

This aberrant expression within pigment cells interferes with an intermediate stage of a well-characterized molecular pathway that governs coat color, the same pathway that functions in other mammals with orange pigmentation.

In those species, conventional orange mutations disrupt an earlier phase of this pathway; in cats, the sex-linked orange mutation disrupts a subsequent phase.

“Undoubtedly, this represents a highly unconventional mechanism, resulting in the misexpression of a gene within a particular cellular context,” Dr. Kaelin observed.

The findings of this research initiative are detailed in a publication released this week in the esteemed journal Current Biology.

_____

Christopher B. Kaelin et al. Molecular and genetic characterization of sex-linked orange coat color in the domestic cat. Current Biology, published online May 15, 2025; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.04.055