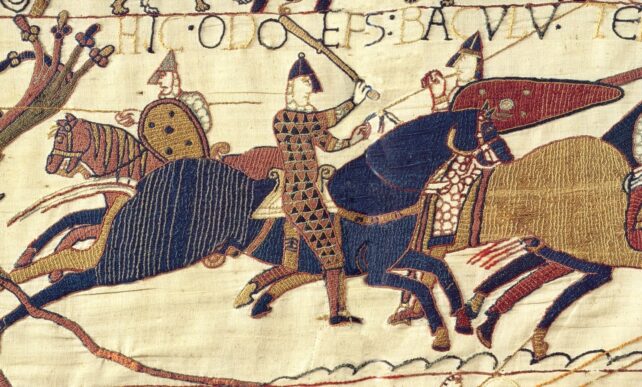

The Bayeux Tapestry, a monumental textile artifact meticulously embroidered to chronicle events culminating in the pivotal Battle of Hastings in 1066, has long been shrouded in enigma. However, this once-obscure artwork may have finally had its intended purpose illuminated.

While scholarly consensus largely posits that the tapestry was conceptualized by ecclesiastics residing at St Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury, England, and meticulously crafted by a cadre of proficient seamstresses, its precise raison d’être and original placement remain subject to considerable debate.

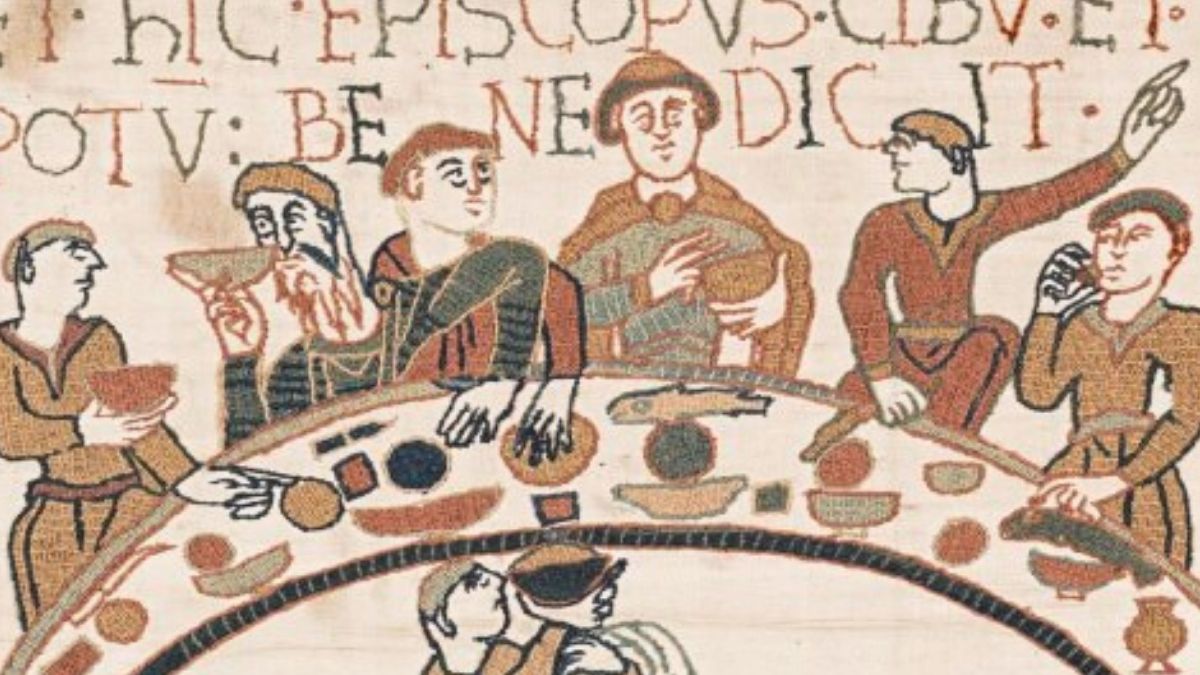

In a recent publication, historian Benjamin Pohl articulates his hypothesis: he postulates that the tapestry served as a narrative backdrop for communal meals at St Augustine’s, or a comparable monastic institution.

“My inquiry centered on whether a refectory environment could offer an explanation for some of the apparent and confounding discrepancies identified within prevailing scholarship,” Pohl elucidates, referencing the communal halls designated for shared repasts among monks.

“Much like in contemporary society, mealtimes during the medieval era were consistently significant junctures for social communion, collective contemplation, charitable acts, and amusement, alongside the reinforcement of shared identities. Within this context, the Bayeux Tapestry would have found an exceptionally fitting locale.”

Although definitive proof of the Bayeux Tapestry’s tenure at St Augustine’s is absent, Pohl indicates that numerous indicators suggest its former presence adorning the walls of the abbey’s refectory.

The sheer immensity of the tapestry—exceeding 68.4 meters (224 feet) in length and weighing approximately 350 kilograms (772 pounds)—necessitates its mounting directly against a robust wall for effective exhibition.

Prior scholarly propositions had suggested its perpetual domicile within the eponymous Bayeux Cathedral, where it was discovered during the 15th century. However, Pohl points out that the cathedral’s vaulted bays and colonnades presented “one of the least conducive settings for the display of the colossal embroidery.”

The tapestry was likely conceived with a religious viewership in mind, Pohl contends, as “its conspicuous (and perhaps intentional) political neutrality and absence of partisan bias… appear difficult to reconcile with the self-definition and identity of England’s post-Conquest aristocracy.”

Furthermore, its varied Latin inscriptions, while elementary, would have demanded a level of erudition not commonly possessed by 11th-century nobles. Monks, conversely, would have navigated the tapestry’s inscriptions with considerable ease.

A monastic audience becomes even more plausible considering the stringent regulations governing monks during mealtimes: they were obligated to maintain absolute silence, even resorting to sign language for requests such as passing the salt. It is conceivable that the tapestry served as a form of didactic, edifying accompaniment to their meals.

“With the monastic community of St. Augustine’s as its primary audience, the Bayeux Tapestry did not have to serve as a vehicle for the narratives of patriotism and national pride/resentment that modern commentators attribute to it,” Pohl observes.

Instead, he posits that its narrative arc could be interpreted as “one that illustrated divine providence at work through the actions of individuals, paralleling how scriptural passages and other forms of historical or hagiographical accounts were conveyed to them during their meals.”

The refectory at St Augustine’s would have presented an optimal setting for the exhibition of such an unwieldy artistic creation: boasting a minimum of 70 meters of internal wall frontage, the edifice possessed ample capacity for the tapestry’s display, even accounting for a potential final, missing segment extending several additional meters.

During the 1080s, plans were laid for an improved refectory at the abbey, yet a series of impediments thwarted its realization. Initially, the premature demise in 1087 of St Augustine’s inaugural post-Conquest abbot, Scolland (a fervent proponent of the renovation), proved a setback.

Subsequently, the death of Scolland’s unpopular successor, Wido, against whom the monks had openly revolted, left the abbatial position vacant for over a decade.

And upon the eventual appointment of Hugh I to the role, prevailing exigencies at St Augustine’s necessitated a redirection of priorities, delaying the refectory’s completion until the 1120s.

It is conceivable that, amidst this protracted construction period, Pohl suggests, the tapestry was put into safekeeping and subsequently faded from the collective consciousness of the monastic community.

“Consequently, the Tapestry might have been stored for over a generation and subsequently overlooked until its eventual transference to Bayeux three centuries later,” Pohl remarks.

This circumstance could elucidate its survival through various calamities that befell the abbey—a conflagration, seismic activity, and a 13th-century refurbishment—as well as its conspicuous absence from any documented records until its appearance in a Bayeux inventory in 1476.

“There remains no definitive method to ascertain the Bayeux Tapestry’s whereabouts prior to 1476, and it is possible that such proof will never emerge,” Pohl explains.

“However, the evidence adduced herein positions the monastic refectory of St Augustine’s as a compelling candidate.”

The comprehensive Bayeux Tapestry is accessible for viewing on Wikipedia, via this link.