A comprehensive genomic investigation, analyzing over 300 genomes, has pinpointed the timeframe of interbreeding between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans. This interaction commenced approximately 50,500 years ago and persisted for roughly 7,000 years, ceasing as Neanderthals began their extinction. The consequence of this genetic exchange is evident today in Eurasians, who carry a significant proportion of genes derived from our Neanderthal predecessors, constituting between 1% and 2% of their entire genetic makeup.

Neanderthal man. Image credit: Mauro Cutrona.

Current sequencing efforts of Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes have illuminated substantial genetic introgression between these ancient hominin species and the ancestors of modern humans. Concurrently, researchers have noted that Neanderthal genetic contributions are not uniformly distributed throughout the human genome.

Furthermore, specific genomic segments, referred to as “archaic deserts,” are notably devoid of Neanderthal DNA, while other regions display a pronounced presence of Neanderthal genetic variants, potentially indicative of advantageous adaptive mutations.

However, a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of this ancient genetic admixture, including the influence of evolutionary forces such as genetic drift and natural selection on these observed patterns, remains an area requiring further elucidation.

“The temporal aspect is of considerable importance, as it directly impacts our comprehension of the timing of human migration out of Africa. This is particularly relevant given that the majority of non-African populations today inherit between 1% and 2% of their ancestry from Neanderthals,” stated Dr. Priya Moorjani from the University of California, Berkeley.

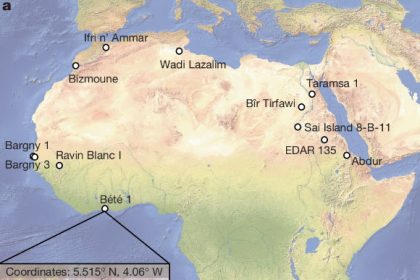

“It also provides insights into the peopling of regions beyond Africa, an area typically explored through the examination of archaeological artifacts or fossil evidence from various global locations.”

“The extended duration of this gene flow might help elucidate, for instance, the observation that East Asians possess approximately 20% more Neanderthal genes than individuals of European and West Asian descent.”

“If modern humans embarked on eastward migrations around 47,000 years ago, as suggested by archaeological discoveries, they would have already incorporated Neanderthal genes through interbreeding.”

In the course of this investigation, Dr. Moorjani and her team meticulously analyzed genomic data obtained from 59 ancient individuals, whose samples ranged from 45,000 to 2,200 years before the present day, alongside data from 275 geographically diverse contemporary individuals.

Their analysis focused on the prevalence, extent, and spatial distribution of Neanderthal ancestral segments across these diverse datasets over time.

The researchers’ findings indicate that the overwhelming majority of Neanderthal genetic contribution can be attributed to a singular, extended period of shared gene flow that likely occurred between 50,500 and 43,500 years ago, a timeframe that aligns with archaeological evidence suggesting the contemporaneous presence of both modern humans and Neanderthals in Europe.

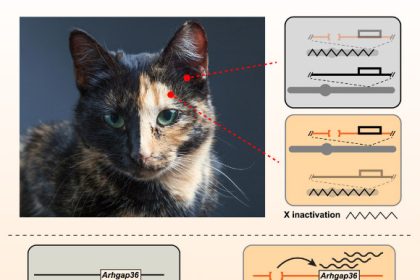

Moreover, their results demonstrate that Neanderthal genetic inheritance underwent vigorous natural selection—encompassing both advantageous and disadvantageous pressures—within a mere 100 generations following the initial gene flow, with a particularly pronounced effect observed on the X chromosome.

“Our research indicates that the period of genetic intermingling was quite intricate and potentially spanned a considerable duration,” commented Dr. Benjamin Peter, a researcher affiliated with the University of Rochester and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

“It is plausible that distinct groups may have diverged during the 6,000- to 7,000-year interval, with certain populations continuing their interbreeding for an even longer stretch.”

“However, the model that best fits the available data points to a single, unified period of gene flow.”

“One of the most significant discoveries from this study is the precise temporal estimation of Neanderthal admixture, which was previously approximated using either singular ancient samples or analyses of present-day individuals,” explained Dr. Manjusha Chintalapati, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley.

“No prior attempt had been made to integrate and model all available ancient samples in conjunction.”

“This comprehensive approach enabled us to construct a more complete historical narrative.”

“We have identified certain Neanderthal genomic regions that are remarkably prevalent, possibly due to their beneficial impact as early modern humans began to explore novel environments outside of Africa.”

“These include genes associated with immune system function, skin pigmentation, and metabolic processes.”

“Conversely, there exist substantial portions of the genome that are entirely devoid of Neanderthal genetic material.”

“These specific regions emerged rapidly subsequent to the gene flow and were also absent from the earliest identified genomes of modern humans, dating back 30,000 to 45,000 years.”

“It is probable that numerous Neanderthal genetic sequences proved detrimental to humans and were consequently subjected to intense and swift negative selection by evolutionary pressures.”

“The diversification of human populations outside of Africa may have commenced during or shortly after the period of Neanderthal gene flow. This could, in part, account for the varying levels of Neanderthal ancestry observed among non-African populations and also reconcile our temporal findings with archaeological evidence indicating the presence of modern humans in Southeast Asia and Oceania by approximately 47,000 years ago,” elaborated Dr. Peter.

“Further investigation into ancient genomes from Eurasia and Oceania could significantly enhance our understanding of the timeline for human expansion into these regions.”

The findings of this research have been published in the esteemed journal Science.

_____

Leonardo N.M. Iasi et al. 2024. Neanderthal ancestry through time: Insights from genomes of ancient and present-day humans. Science 386 (6727); doi: 10.1126/science.adq3010