A pivotal consideration for the potential habitability of exoplanets revolves around the enduring stability of their host celestial bodies. Certain stars, characterized by immense mass, exhaust their hydrogen reserves with remarkable rapidity, typically within a mere span of a few million years.

Rigel, a luminous blue supergiant situated within the constellation Orion, exemplifies this category. Its luminosity is projected to persist for approximately 10 million years, a fleeting timeframe for the emergence of life on any associated planets.

Conversely, stars such as red dwarfs possess lifespans far exceeding the current age of the cosmos. However, their propensity for violent flaring events may present significant obstacles to the habitability of their planetary systems.

Stars akin to our Sun appear to occupy an advantageous position in this cosmic spectrum, maintaining their steady luminescence for an estimated 10 billion years before transitioning into red giants. It is evident that the sustained stability offered by our Sun has facilitated the evolution of complex life.

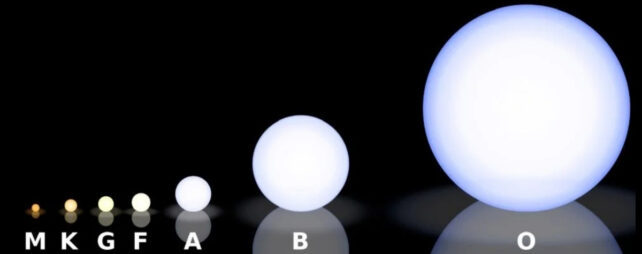

The Sun is classified as a G-type star, also recognized as a yellow dwarf. These stellar classifications are prevalent, as are their slightly less massive counterparts, K-type stars, commonly referred to as orange dwarfs. Exhibiting cooler temperatures than the Sun but warmer than red dwarfs, these stars, much like G-type stars, are distinguished by their longevity and inherent stability.

While solar-type stars persist on the main sequence for approximately 10 billion years, K-type orange dwarfs can continue their existence for many tens of billions of years, with lifespans ranging from roughly 20 to 70 billion years.

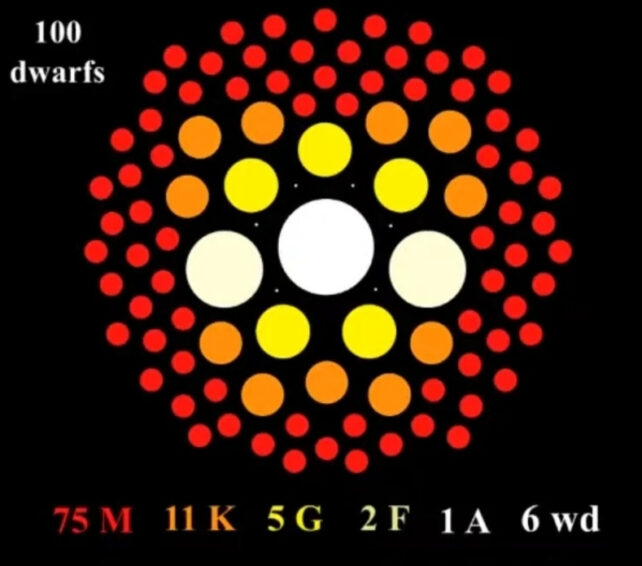

This extended period of stability positions them as significant subjects of interest for astronomers investigating stellar habitability. In the immediate celestial vicinity of our solar system, K-type stars are approximately twice as numerous as G-type stars.

A collective of astrophysicists has undertaken a comprehensive survey of over 2,000 K-type stars in proximity to our Sun. Detailed spectral analyses were acquired for a substantial number of these stars, yielding insights into their ages, rotational rates, thermal characteristics, and galactic positions within the Milky Way. These parameters demonstrably influence the potential habitability of orbiting exoplanets.

“This survey represents the inaugural exhaustive examination of thousands of the Sun’s lower-mass stellar relatives,” stated lead author Carrazco-Gaxiola in a press release.

“These celestial bodies, often termed ‘K dwarfs,’ are ubiquitously distributed throughout the cosmos and furnish a sustained, tranquil environment for their companion planets.”

The endeavor to identify habitable worlds is a monumental undertaking. The Milky Way galaxy harbors at least 100 billion stars, and potentially as many as 400 billion, although definitive figures remain elusive.

Any methodology that assists researchers in efficiently navigating this vast stellar population is invaluable. This is particularly true given the considerable resources required for the detailed observational studies of individual stars and exoplanets necessary to ascertain habitability.

Findings such as these contribute significantly to refining the search parameters, enabling astronomers to allocate observational resources with greater efficacy.

“We present a spectroscopic characterization of 580 K dwarfs within a 33 parsec radius, observed utilizing the CHIRON echelle spectrograph mounted on the SMARTS 1.5m telescope,” the authors elucidated in their publication.

According to the NASA Exoplanets Archive, a mere 7.5% of these stars, equating to 44 individuals, are currently known to host confirmed exoplanets.

“Our findings pinpoint 529 mature, inactive K dwarfs as prime candidates for investigations focused on terrestrial planets, thereby establishing a critical resource for exoplanet habitability studies within the solar neighborhood,” the researchers explained.

An additional 1.5-meter telescope situated in Arizona, the Tillinghast Telescope, also contributed to this extensive survey. Both instruments are equipped with high-resolution echelle spectrographs, and their deployment in opposing hemispheres provided the research team with comprehensive all-sky observational coverage.

“The CHIRON spectrograph aboard the SMARTS telescope in Chile, coupled with the TRES spectrograph on the Tillinghast Telescope in Arizona, function as highly complementary instruments,” remarked Allyson Bieryla, an astronomer affiliated with the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian.

“The synergistic advantage of possessing these two telescopes in diametrically opposed hemispheres is that it grants us access to the entirety of K-dwarf stars across the celestial sphere.”

Variations in galactic metallicity influence habitability across different regions of the Milky Way. This survey also precisely determined the spatial distribution of each surveyed star. The thin disk, where the majority of the galaxy’s stellar population, including K-dwarfs, resides, exhibits more favorable metallicity conditions.

K-type stars constitute approximately 11% of the stellar population within a 33 parsec radius, equivalent to roughly 108 light-years. Not only do they surpass Sun-like stars in longevity, but they also exhibit diminished flaring activity and reduced ultraviolet emissions compared to red dwarfs (M dwarfs). Their energetic flares and UV radiation cast doubt upon the habitability of planets orbiting them.

“In contrast to M dwarfs, K dwarfs emit less extreme ultraviolet radiation and demonstrate attenuated flare activity, thereby potentially offering a more serene environment conducive to the atmospheric retention of orbiting planets,” the authors elaborated.

The researchers are particularly focused on identifying evolved, quiescent K-type stars, as these celestial bodies exhibit the least incidence of disruptive flares and high-energy radiation.

Despite the characteristics of K-type stars rendering them favorable targets for habitability studies, they have not garnered the commensurate attention they warrant, according to the study’s authors. Within a radius of approximately 25 parsecs, K-type stars appear to host fewer exoplanets than M dwarfs and Sun-like stars.

This discrepancy is attributed solely to observational bias. Sun-like stars, being intrinsically brighter, facilitate the detection of their orbiting planets. Furthermore, M dwarfs possess a more advantageous planet-to-star mass ratio, which aids in exoplanet detection.

“This survey will serve as the bedrock for subsequent investigations of nearby stars for many decades to come,” stated Distinguished University Professor of Physics and Astronomy Todd Henry, who advises Carrazco-Gaxiola and is a senior author on the research paper.

“These stars and their planetary companions will undoubtedly be the ultimate destinations for spacecraft exploration in the distant future of interplanetary travel.”

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.